Thanks for reading! If you haven’t subscribed, please click the button below:

By subscribing you’ll join over 19,000 people who read Apricitas weekly!

Otherwise, liking or sharing is the best way to support my work. Thank you!

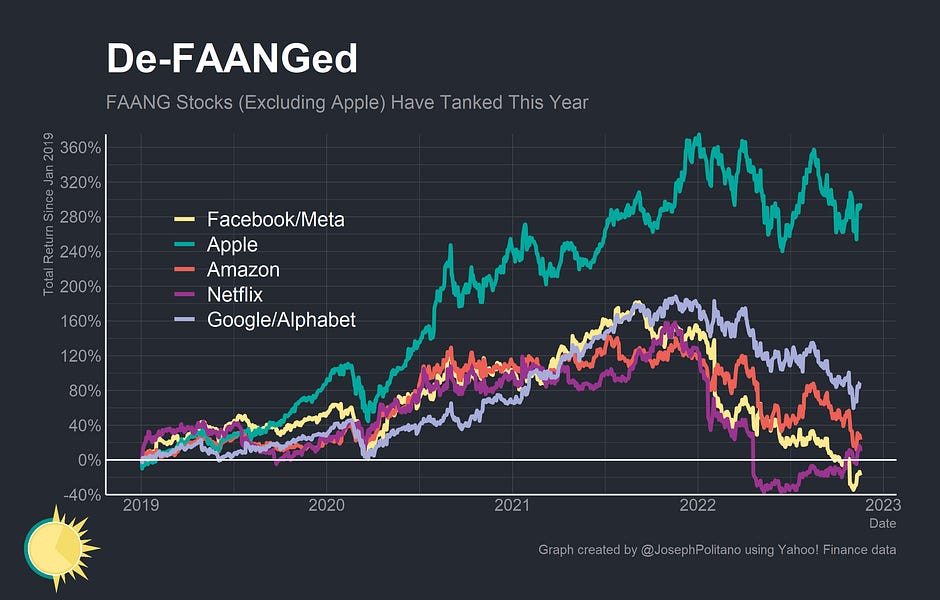

This year has been especially unkind to the tech industry—the banner years of the techno-hype-driven early pandemic have started to come apart. Public and private companies alike are seeing massive declines in their valuations as a reopening offline economy mixes with a worsening economic outlook and souring prospects for many longshot investments.

For a brief moment in 2021 video-conferencing company Zoom had a higher market cap than oil giant ExxonMobil—now Exxon is worth more than nineteen times Zoom. The unassailable giants of the industry look weak—except Apple, all of the former FAANG companies have taken massive hits to their share prices.

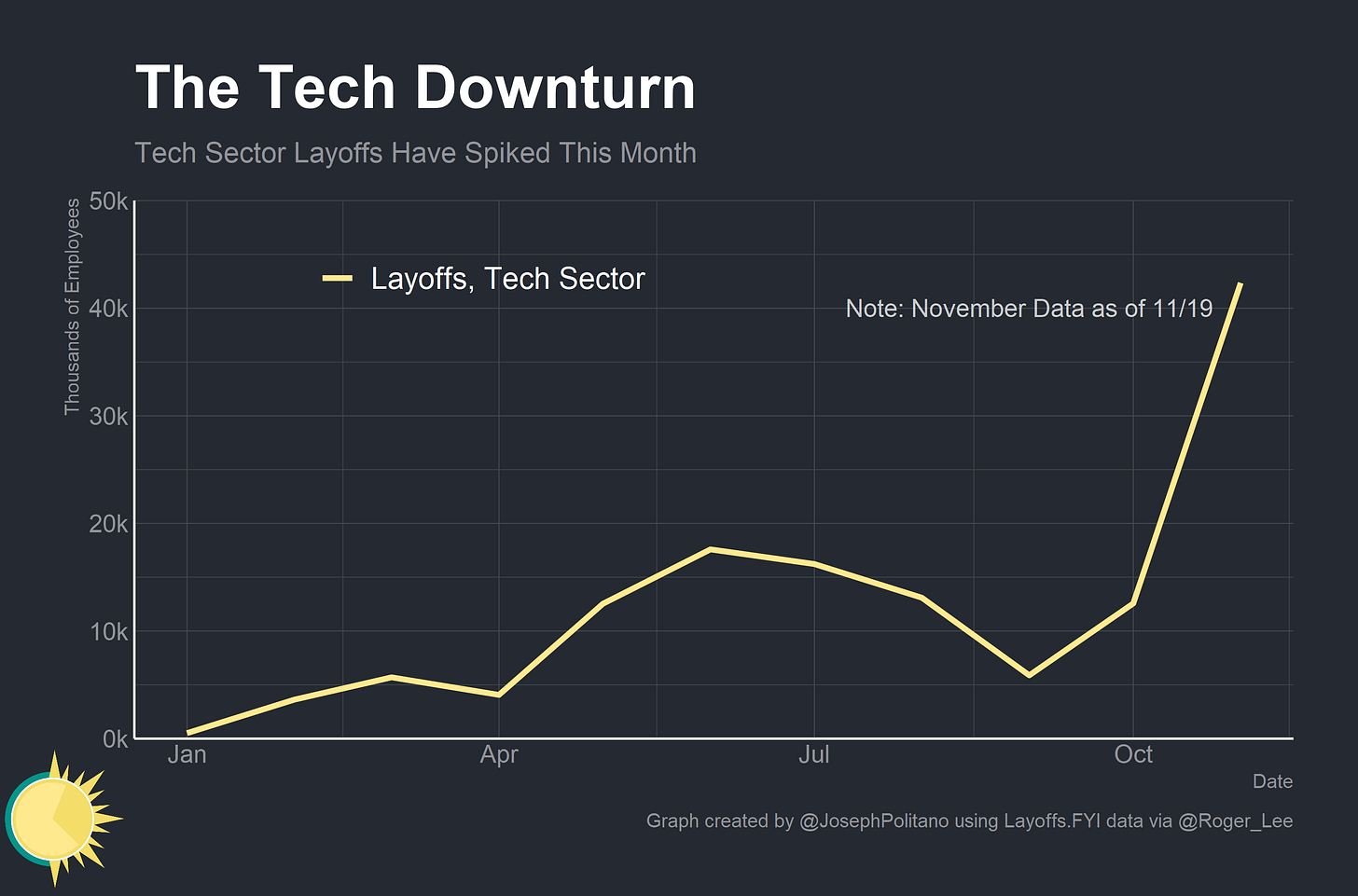

Industry giants are now engaged in formerly-unthinkable programs of aggressive layoffs—11,000 at Meta (formerly Facebook), 10,000 at Amazon, 4,100 at Cisco, 3,700 at Twitter, 1,000 at Salesforce, and another 1,000 at Stripe just so far this month according to Layoffs.FYI. The total number of layoffs sits at above 40,000 this month—double the year’s prior monthly record (and November isn’t even 2/3 over!). The mood has noticeably shifted in Silicon Valley—but what does a tech downturn mean for the economy at large?

Discussing the tech-cession is hard because talking about tech as a monolith is hard—it is difficult to imagine two companies with more radically different business models than Meta and Amazon, yet they are both lumped in together as tech companies. Is Redfin a tech company, a real estate company, or a finance company—and where should Redfin layoffs be attributed? Most—though by no means all—tech workers get classified in the information sector (alongside Hollywood, the news media, and telecom giants), and that industry has actually seen normal layoff numbers through September of this year (besides the large spike in January).

Still, the sectoral numbers put into relief how large this month’s layoffs were. Just the job losses at Meta and Twitter were nearly 15,000—compared to 21,000 total layoffs in the entire information sector in September.

Those Meta and Twitter layoffs would represent about 4% of employees in the “internet publishing” industry, which encompasses many social media companies. The entire batch of tech layoffs so far this month would represent 3% of internet-related information sector jobs, though it is unrealistic to assume that all laid-off workers come from the sector and none would get re-employed in the industry.

Still, it begs the question—how much should we care about the tech-cession from a broader economic perspective? Plenty of industries have more layoffs than this on a monthly basis. Is this mostly a man-bites-dog media story driven by the fact that people don’t expect Facebook to downsize as many regular companies have to?

That seemed to be the thesis of Goldman Sachs’ research note on the issue last Thursday. Although tech companies make up 1/4 of the S&P 500 they make up only a meager 0.3% of American employment. The tech industry “is not large enough for tech layoffs to cause a meaningful labor market slowdown on their own” and “tech job cuts have frequently spiked without a corresponding increase in cuts in other sectors and have otherwise been a coincidental indicator,” the note said.

That may be true, but the information sector makes up 5.4% of US GDP—more than the entire construction industry (3.9%) or food service and accommodation (3.1%). The number of workers laid off may be few but the impact on aggregate spending could be much larger—compensation for employees in the internet publishing industry is more than four times the US average. Plus, the drop in labor demand alongside losses in the value of stock options could pull compensation down significantly this year even if the overall number of workers in the industry remains relatively unchanged—as we may have already seen in Q1 data. That could have big spillover effects on the rest of the economy—as would the negative wealth shock caused by lower valuations at big tech companies. This isn’t an invitation to panic—but it is an invitation to take a slowdown in one of America’s biggest industries with the seriousness it deserves.

It’s hard to tell. Tighter monetary policy might be hurting early-stage startups more thanks to its discouragement of risky investment, but much of the broader industry anxiety stems from mature firms like Netflix, Meta, and Amazon not unprofitable startups. Much of the failures seem to stem from difficulties in forecasting and managing demand amidst a rapidly changing world—and tech companies got stuck at the forefront of the change. Just as macroeconomic factors outside of tech companies’ control made them superstars at the start of COVID, macroeconomic factors outside their control arguably present their biggest threat now.

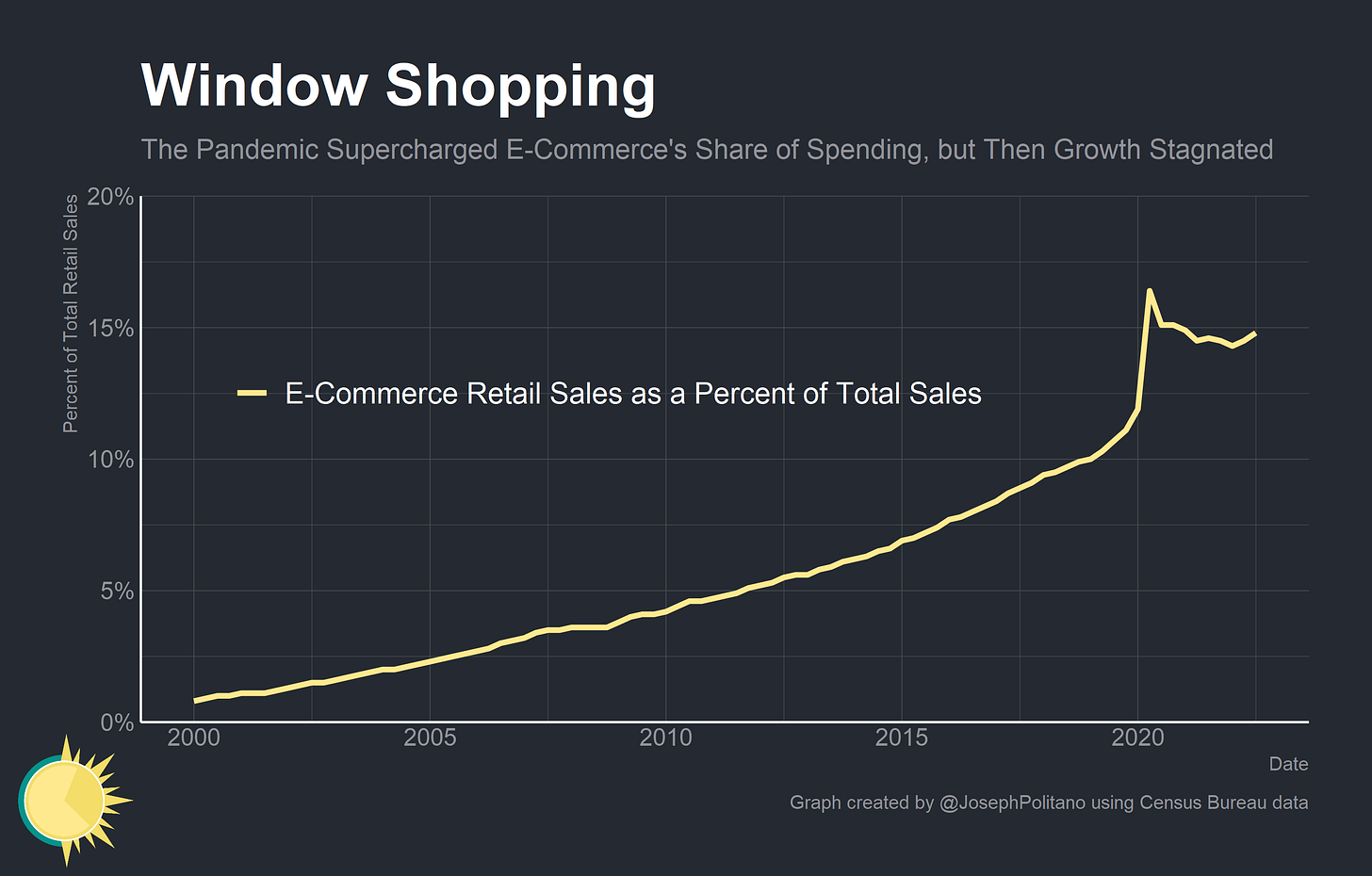

Still, there are some reasons for optimism. Although the hoped-for permanent shift towards e-commerce hasn’t manifested exactly as many tech companies hoped, it is true that the pandemic accelerated e-commerce adoption in a way that has seemingly boosted its long-run consumer penetration.

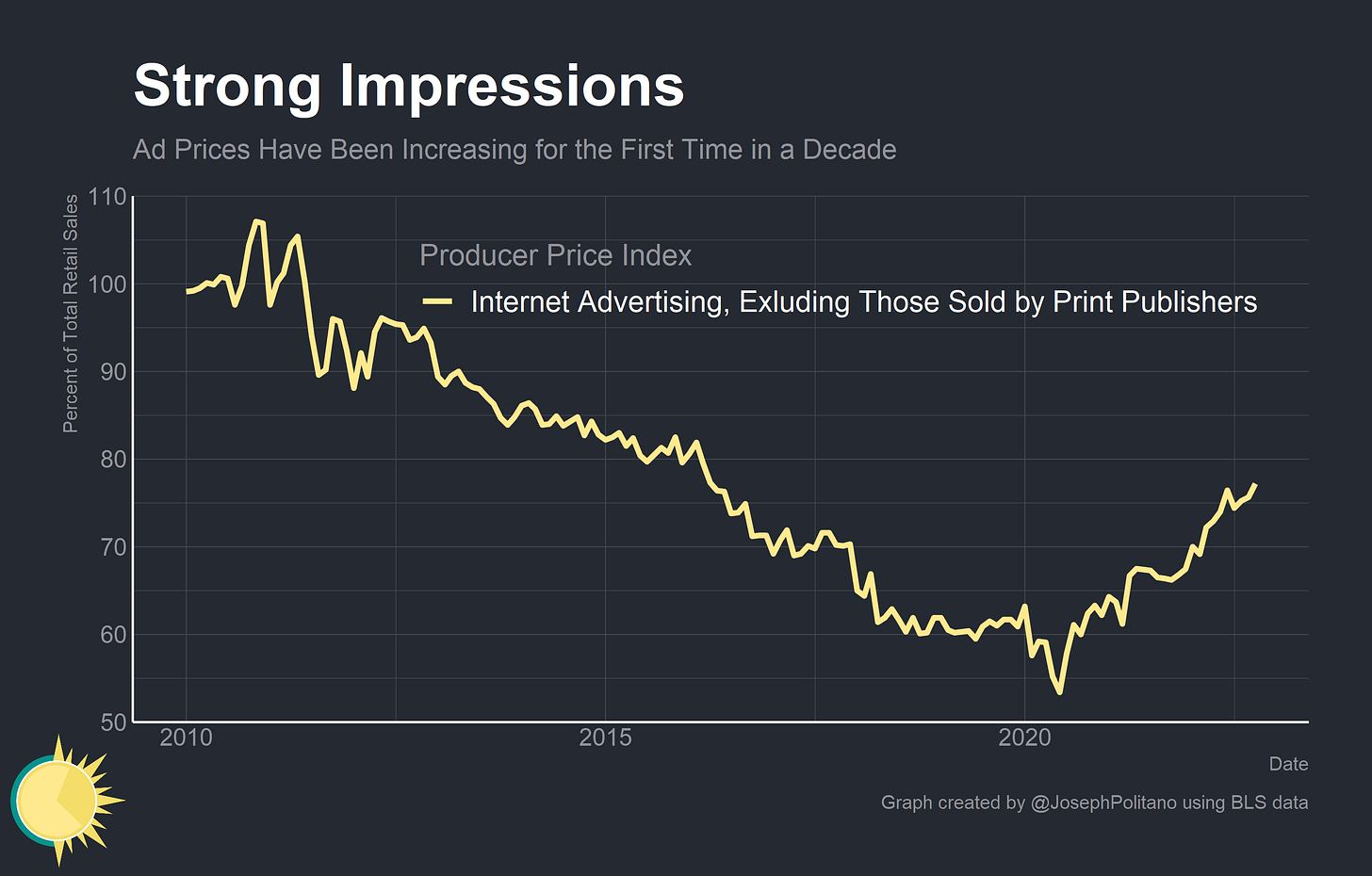

Plus, the price for advertising—many digital companies’ biggest sources of revenue—has held up fairly well despite elevated macroeconomic risk. Usually, ad budgets are the first to go when the economy sours, hence why many big tech companies are sensitive to recession risk. Elevated digital ad prices therefore compose the kind of tailwind many tech companies hope to retain as long as possible.

The tech-cession isn’t likely to have as big an impact as people on big tech platforms make it out to be—but just because companies are headquartered in Silicon Valley doesn’t keep them in a walled garden separate from the rest of the economy. Take US chip manufacturing, which has been sputtering in part as weakening demand hits global tech and electronics industries. It’s another good reminder to keep attuned to risks across sectors—as we’ve been reminded a lot recently, “move fast and break things” sometimes doesn’t work out too well.

.svg-225x125.png)