ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/S. Dagnello (NRAO/AUI/NSF)

Astronomers have caught a red giant star going through its final death throes in unprecedented detail, revealing an unusual feature. The star, known as V Hydrae (or V Hya for short), ejected six distinct rings of material, according to a preprint accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. The specific mechanism of these mysterious “smoke rings” formed is not yet understood. Still, the observation could potentially shake up current models for this particular late stage of stellar evolution and shed further light on the fate of our own Sun.

“V Hydrae has been caught in the process of shedding its atmosphere—ultimately most of its mass—which is something that most late-stage red giants do,” said co-author Mark Morris, an astronomer at UCLA. However, “This is the first and only time that a series of expanding rings has been seen around a star that is in its death throes—a series of expanding ‘smoke rings’ that we have calculated are being blown every few hundred years.”

Red giants are one of the final stages of stellar evolution. Once a star’s core stops converting hydrogen into helium via nuclear fusion, gravity begins to compress the star, raising its internal temperature. This process ignites a shell of hydrogen burning around an inert core. Eventually, the compression and heating in the core cause the star to expand significantly, reaching diameters between 62 million and 620 million miles (100 million to 1 billion kilometers). The surface temperatures are relatively cool by stellar standards: a mere 4,000 to 5,800 degrees F (2,200 to 3,200 degrees C). So these stars take on an orange-red appearance, hence the red giant moniker.

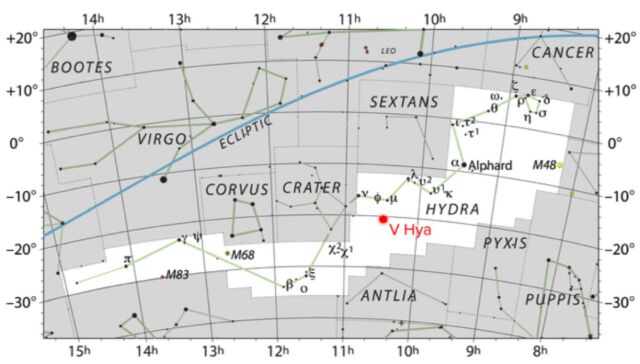

IAU and Sky & Telescope

Eventually, the helium in a red giant’s core will be spent, and the core will shrink again. The star then becomes an asymptotic giant branch (AGB) star (the final red giant stage). The interior structure of an AGB star consists of a central core of carbon and oxygen, a shell where fusion is turning helium into carbon, and another shell where hydrogen is turning into helium. These stars typically produce dramatic pulses of increased brightness every 100 to 1,000 days. In addition, intense surface winds cause a gaseous cloud known as a circumstellar envelope to form around the star.

Those intense stellar winds will eventually expel the atmosphere and stellar envelope, and the star will become a white dwarf star within a planetary nebula. The faster the rate at which an AGB star loses its mass, the closer it is to that final transition. Our Sun will eventually become a red giant in about 5 billion years, eventually progressing to an AGB before finally evolving into a planetary nebula with a white dwarf star at its center.

That’s the process as astronomers have understood it for years. The unusual characteristics of V Hya have them rethinking matters, however. Located 1,300 light-years away in the constellation Hydra, V Hya is a carbon-rich star, meaning its atmosphere contains more carbon than oxygen. It has a high loss rate for its mass, so astronomers surmise that it’s probably in the process of shedding its atmosphere to become a planetary nebula.

ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/S. Dagnello (NRAO/AUI/NSF)

This AGB star is also intriguing because every eight years or so, there are large plasma eruptions, and sharp decreases in brightness occur roughly every 17 years. These events suggest the presence of a companion star that is barely visible. (The dips in brightness could be caused by a cloud linked to this second star passing in front of V Hya.)

This latest study combines data from the Hubble Space Telescope with observations using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), incorporating infrared, optical, and ultraviolet data to capture V Hya’s death throes across multiple wavelengths. The star is far away and surrounded by dense dust, but the higher resolution capabilities of ALMA revealed its rings and outflows in great detail.

The timing was also serendipitous. “V Hya is in the brief but critical transition phase that dying stars go through at the end of their lives,” said co-author Raghvendra Sahai, an astronomer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “It’s the phase when they lose most of their mass. It’s likely that this phase does not last very long, so it is difficult to catch them in the act. We got lucky with V Hya, and were able to image all of the different activities going on in and around this star to better understand how dying stars lose mass at the end of their lives.”

Sahai and his co-authors found that the star is shedding its atmosphere by blowing a series of smoke rings, which have expanded outward over the last 2,100 years or so to form a dusty disk-like region around V Hya. The team dubbed that structure DUDE (disk undergoing dynamical expansion).

Their observations also revealed high-speed blasts of gas expelled from the star in opposite directions, perpendicular to the smoke rings, forming two hourglass-shaped structures. These structures are expanding rapidly at more than half-a-million miles per hour (240 km/s). “The discovery that this process can involve ejections of rings of gas, simultaneous with the production of high-speed intermittent jets of material, brings a new and fascinating wrinkle to our understanding of how stars end their lives,” Morris said.

All of this suggests that the star is undergoing a particularly rapid evolution, which runs counter to the current model. “Our study dramatically reveals that the traditional model of how AGB stars die—through the mass ejection of fuel via a slow, relatively steady spherical wind over 100,000 years or more—is at best incomplete, or at worst, incorrect,” said Sahai. “It is very likely that a close stellar or substellar companion plays a significant role in their deaths. In the case of V Hya, the combination of a nearby and a hypothetical distant companion star is responsible, at least to some degree, for the presence of its six rings, and the high-speed outflows that are causing the star’s miraculous death.”