Jonathan Blake was only 32 years old at the time, but the meeting the lawyer held with a senior British Treasury minister in 1987 has helped create more millionaires than the UK’s National Lottery.

At issue was a complex structure that Mr Blake had designed to allow the fledgling private equity industry to set up funds in the UK without losing the low-tax treatment it had until then enjoyed offshore. It contained a crucial detail for dealmakers from the worlds of private equity and venture capital: their personal payouts, often eye-watering sums known as carried interest or “carry”, would be taxed as capital gains rather than income.

Tax authorities had objected, saying that if other business and industry leaders paid income tax on their bonuses, private equity executives should do the same.

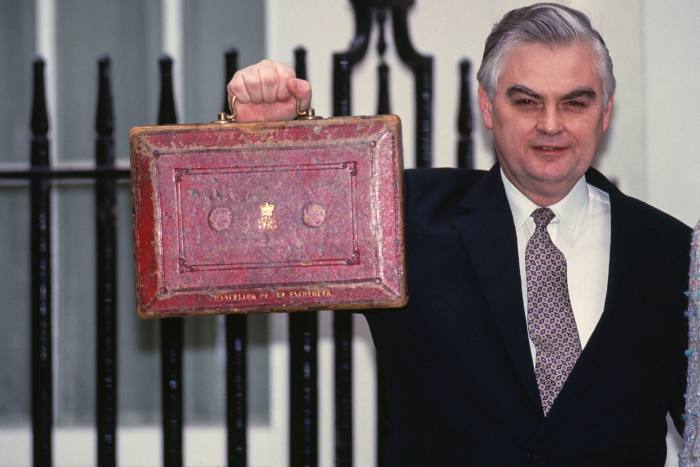

Mr Blake, who had been summoned to defend his scheme, took a chance. “If you don’t agree”, he told Norman Lamont, then the chief financial secretary, “we’ll just carry on using offshore structures.” An awkward silence followed.

“It was quite terrifying because I had clients riding on this,” Mr Blake, now 66 and a lawyer at Herbert Smith Freehills, says. “I suppose when you’re that age, you’re willing to take risks.”

Mr Lamont blinked first. It led to an agreement that even today, allows private equity executives in the UK to pay lower tax rates, on their multi-million-pound bonuses, than workers pay on annual wages over £50,000. They receive similarly tax-advantaged treatment in the US, and many European countries which have subsequently adopted their own carried interest tax regimes.

The UK agreement, with its official sanction and its parallels with the US where private equity was born, became the bedrock on which the then-nascent industry could establish itself and expand rapidly outside America. And although politicians from President Barack Obama to his successor, Donald Trump, have promised to dismantle a tax system that has concentrated wealth in the hands of a powerful few, progress has been slow.

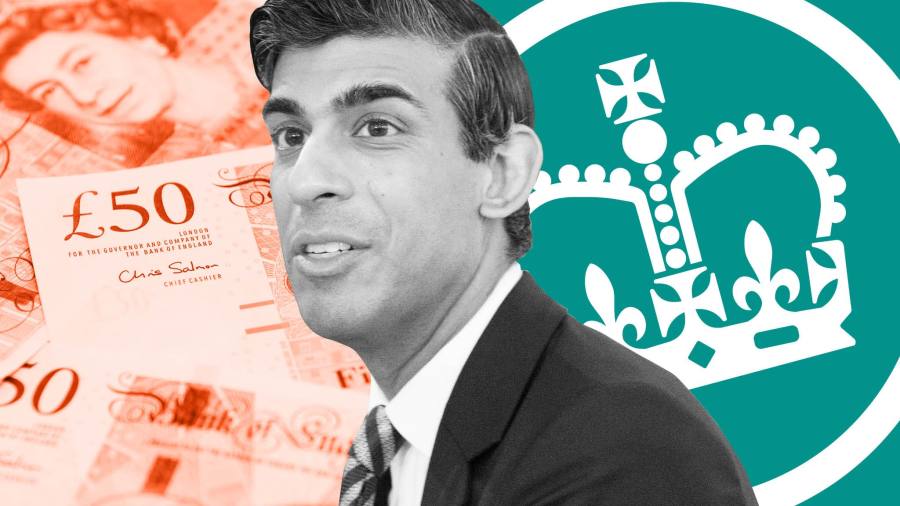

Coronavirus could potentially change that. As the unprecedented levels of government spending unleashed by Covid-19 prompts a desperate need for revenue, the UK has launched a review of capital gains tax which threatens to hit private equity by raising the rate closer to, or in line with, income tax levels. In July, Rishi Sunak, the UK chancellor, asked the Office of Tax Simplification to look at “the interactions of how [capital] gains are taxed compared to other types of income.”

Any move by the UK could set a marker for how the financial sector and the wealthy will be taxed in the post-pandemic environment.

The review rang alarm bells among industry lobbyists now gearing up to oppose any changes. A briefing note circulated by the British Private Equity and Venture Capital Association to its members, argues that tax rises may drive the industry — which it says has invested £43bn in more than 3,230 UK companies in the past five years — out of the UK and reduce entrepreneurial activity.

Several executives who benefit from the tax break are already bracing themselves for its abolition with consultation on the review ending on Monday. Any reforms could, if backed by ministers, be introduced as early as next year.

“It would be powerful if you had a major country that is a big financial centre saying, we’re going to change this,” says Robert Palmer, executive director of the advocacy group Tax Justice UK. “It would bolster attempts to do it elsewhere, even in the US. Countries do look to others on these issues, particularly [to] the UK.”

Political statement

In Britain, £2.3bn in carried interest was paid to a group of 2,000 people in 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, according to research by the University of Warwick and the London School of Economics. That is an underestimate, the report’s authors say, since it excludes some “non-domiciles” whose permanent home is registered overseas and any carry payments that stem from fees and dividends, which are taxed as income.

Taxing it as income would have raised an extra £440m, assuming people paid rather than leaving the country to avoid it, the report calculated. In the US taxing carried interest as ordinary income would have raised an extra $1.4bn in 2020, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

It is a relatively small amount for a UK government whose deficit will climb to £350bn next year because of the costs of the pandemic, more than six times the level forecast in March, according to an Institute for Fiscal Studies forecast. But its significance may be more political than economic with governments likely to face considerable pressure to push more of the burden post-pandemic on to the richest members of society. Capital gains is, in general, a tax on the affluent: in 2017‐18, 62 per cent of its returns came from people who made gains of £1m or more.

“The politics of this are really not in favour of capital gains or carried interest right now,” says Mr Palmer. “The people benefiting have done the least worst during [the pandemic]. It would be hard to do broad-brush tax rises without also doing something at the top.”

These lower tax rates have their roots in a financing model for oil and gas exploration in the US in the early 20th century. An “exploration fund”, sometimes for wildcat drilling, would receive two types of contribution: money, often from wealthy individuals, and the provision of services. Partners in that fund would pay capital gains tax on any profits, whether they had contributed the capital or the labour.

In the modern version, investors such as pension funds provide money to private equity funds, and dealmakers employed by buyout groups provide services — the buying and selling of companies.

Because profits from the fund come from the sale of assets, the industry’s US lobby group the American Investment Council argues, it is right to tax carried interest as a capital gain whether its recipient’s contribution to the fund was money, services — which it calls “sweat equity” — or both.

“One prickly aspect of carried interest is that the fund manager is getting capital gains treatment in return for their services which, in any other setting, is ordinary income — eg, your pay cheque,” says Dean Galaro, a Denver-based lawyer at Perkins Coie.

The argument for capital gains treatment also rests on the idea that executives inject some of their own money into funds, making profits a return on investment.

Raising the rate in line with income tax would break that link — though, in any case, some private equity executives invest using non-recourse loans which shield their personal wealth from any losses if bets go wrong.

In many cases “there’s not much of a basis for saying they’re taking the risk of an investor; they’re not,” says Jon Moulton, one of the UK’s best-known private equity executives. “Carried interest historically has justified a capital-gains rate . . . because it generates an incentive to invest, but if the private equity manager is not investing any capital, that argument becomes rather difficult to sustain.”

Another London-based former private equity executive, puts it more starkly. “Everybody in the industry knows [the tax treatment] is the result of good lobbying, particularly in America,” he says. “While America treats it as a capital gain, everybody’s going to do the same.”

A change in the US, where vigorous lobbying has kept the tax break intact, is far from inevitable, even under a Joe Biden administration. Control of the Senate is on a knife-edge. Elizabeth Warren’s so-called Stop Wall Street Looting bill, which would have ended what it called the “carried interest loophole”, stalled after it was introduced in the Senate last year.

Lucrative sector

Low tax on carried interest is just one part of what is often a lucrative pay packet for private equity executives that has helped turn the industry into a magnet for everyone from ambitious business school graduates to experienced bankers, lawyers, consultants and corporate executives.

Private equity groups charge a management fee, often 2 per cent of the fund’s total value, to pension funds and other investors, and use this to pay salaries and bonuses as well as operating costs. The money left over — which, for megafunds containing $10bn or more of capital, is often a sizeable sum — can be handed to the firms’ most senior executives, though it is taxed as income.

Dealmakers also pay income tax on payments derived from the dividends and fees paid by companies they own. But they pay the lower capital gains rate on their 20 per cent share of the profits made when the private equity fund sells the companies it owns.

The number of active private equity firms worldwide has more than doubled in the past decade to almost 6,700, and the number of US companies that they own a stake in has risen by 60 per cent, according to a report published by McKinsey in February. Meanwhile the number of listed companies has fallen dramatically as buyouts take companies private: in the US it is about half its 1996 level.

Against that backdrop, the US, UK, France, Germany and Italy have enshrined in regulation private equity’s tax-advantaged way of paying its people.

In 2018, France cut tax on carried interest to 30 per cent for fund managers relocating to the country, as President Emmanuel Macron’s government sought to lure more firms to Paris in the wake of the UK’s Brexit vote. In 2017 Italy set out tax reforms that specified carried interest would be taxed as investment income at 26 per cent rather than income from services, at up to 43 per cent plus surcharges.

“[Governments] are trying to attract the funds industry as a whole [because] it is recognised as a valuable addition to the economy,” says Laura Charkin, a partner at law firm Goodwin.

The UK has moved tentatively in the opposite direction. In 2015 it singled out carried interest for a special tax rate of 28 per cent, higher than the 18 per cent capital gains rate previously levied. It also banned a system called “base cost shifting” which cut the proportion of gains on which tax is paid. That makes today’s rate, while far below the 45 per cent that many top earners pay in income tax, the highest it has ever been.

An industry that has spent decades fighting for its tax breaks is unlikely to give up easily. Stephen Schwarzman, founder of Blackstone, offered an insight into how highly prized the tax regime was in 2010, when he compared the Obama proposal to raise the tax to “a war”.

But having spent years preserving low tax rates by arguing that carried interest is a special case, the industry lobby could be blindsided by the simplicity of a reform that does not challenge this contention, but simply raises the tax rate for all capital gains. “In that case there would be no rationale for carry to be taxed differently [than other capital gains],” one senior London private equity executive says.

“It would be hard for the industry to fight it,” says a lawyer who has advised private equity groups. “They would be crucified in the court of public opinion if they left the country [in response to a tax rise]. [The firms] need to be in London because you’re not going to get the big law firms and accounting firms moving to support them.”

The BVCA’s response to the consultation says carried interest should continue to be taxed at a lower rate than income because the higher tax rate would be a body blow to entrepreneurialism and the UK’s start-up scene at a time when it is vital to economic recovery. Any change would risk penalising investors unfairly for inflation and leaving the UK out of sync with other countries, potentially driving the industry away, the document says.

“There is a big philosophical and political debate to be had” about whether it is right to tax capital gains less than income, says a lawyer who is advising the industry. “It’s easy to say these people make a lot of money, so why shouldn’t they pay some more tax on it, but I’d rather they were here earning money and paying some tax than not here [at all].”

The industry will have to make its case despite a growing sense of unease, including among some recipients of carried interest, about arguing for low tax when the coronavirus pandemic has widened social and economic divides and left governments in desperate need of funds.

“I think most people even in private equity know that taxes will have to rise,” says a senior London-based private equity executive. “There’s not much you can do about it [and] to an extent it’s fair enough. Maybe it will calm down feelings of inequality.”

Big business in helping executives spend their ‘carry’ bonanzas

Carried interest payments have become so valuable that they have spurned a new niche: private bankers who help arrange everything from mortgages to school advice to life insurance for its recipients.

“When people receive these [payments], often they are life changing,” says Emily Cvijan, a private banker at Investec, who says executives can receive the payouts even in their early thirties.

Years before carry is paid out, potential recipients can use the prospect of a windfall to buy more expensive homes than their salaries alone would permit, using a mortgage product designed especially for private equity executives that factors carried interest in.

“Oxford in particular has cropped up” as a popular destination since the pandemic began, says Ms Cvijan. “People are thinking, does the commute need to be five days a week any more?”

Then there are the real treats. A portion of most carry payments is reserved for a “kind of indulgent purchase” such as cars, horses and art, she says, adding that one executive worked with an international art dealer to build up a collection of rare Japanese paintings.