Five deaths have been linked to the fires.

Deep into its latest battle against ballooning wildfires, Northern California is facing another day under siege, with the huge blazes ripping across the region still growing and still almost completely uncontained.

Five deaths have been linked to the fires, which have forced more than 60,000 people out of their homes, filled the skies with thick smoke and consumed hundreds of homes. More evacuation orders were issued on Friday, including along parts of the Russian River near Santa Rosa.

The fires, burning across more than 771,000 acres, were ignited by lightning during an extraordinary period of nearly 12,000 lightning strikes over several days, which caused about 560 fires, including nearly two dozen major ones. As flames raced toward homes this week, smoke worsened an already oppressive heat wave, lightning strikes sparked new fires, the electrical grid struggled to keep up with demand, and the coronavirus threatened illness in evacuation shelters.

At least four bodies were recovered Thursday, the authorities said, including three from a burned house in a rural area in Napa County and a man found in Solano County. On Wednesday, a helicopter pilot on a water-dropping mission died in a crash in Fresno County.

Firefighters have struggled to contain the largest fires. One group of fires, called the L.N.U. Lightning Complex, doubled in size Wednesday and nearly doubled again on Thursday, growing to 219,067 acres as it stretched across Napa and four surrounding counties. The fires in that grouping have destroyed nearly 500 homes and other buildings, many of them in Vacaville, and are responsible for the four civilian deaths as well as four injuries, according to Cal Fire, the state’s fire agency. Firefighters said those blazes are 7 percent contained.

A combination of fires known as the C.Z.U. Lightning Complex has forced more than 64,600 people in San Mateo and Santa Cruz Counties to evacuate, including the entire University of California, Santa Cruz campus, which was placed under a mandatory evacuation order on Thursday night. The fires have grown to 50,000 acres, consumed at least 50 buildings and are completely uncontained.

East of Silicon Valley, the S.C.U. Lightning Complex, a group of about 20 fires, had spread across 229,968 acres — largely in less populous areas — and was 10 percent contained as of Friday morning, Cal Fire said. Its proximity to San Jose had led to some evacuation orders, and two emergency workers and two civilians have been injured.

Gov. Gavin Newsom, in a video message for the Democratic National Convention on Thursday, called the state’s wildfires an “unprecedented challenge” and linked them to global warming. “If you are in denial about climate change, come to California,” he said.

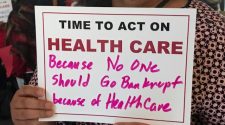

Evacuees seeking shelter must weigh risk of the coronavirus.

A wildfire was raging outside, but inside the evacuation centers there were risks, too.

Natalie Lyons and Craig Phillips had to make a decision Thursday morning as they sat in their ash-coated Toyota Tundra under the smoky orange sky in Santa Cruz.

After fleeing the small town of Felton on Wednesday as a series of wildfires continued to burn along the Central Coast of California, they sought refuge at the Santa Cruz Civic Auditorium, an evacuation site, but the building was full — and Ms. Lyons was scared of contracting the coronavirus in an enclosed, indoor space.

“There’s some people coughing, their masks are hanging down,” said Ms. Lyons, 54, who said she had lung problems. “I’d rather sleep in my car than end up in a hospital bed.”

So that is exactly what the couple did. Their car served as a makeshift bed across the street from the auditorium, and Ms. Lyons tried to get comfortable in the back seat with their Chihuahua-terrier mix and shellshocked cat. “I hardly got any sleep,” she said.

Tens of thousands of people have been forced to evacuate from the rural areas of San Mateo and Santa Cruz Counties, Cal Fire said, and many have struggled to find a place to go, especially with the pandemic still limiting indoor gatherings.

Evacuees further up the coast near Pescadero slept in trailers in parking lots or on the beach overlooking the Pacific Ocean. Others made desperate pleas to family members and friends to take them in, and local authorities said they preferred that people assimilate into so-called quarantine pods rather than brave the virus risks of an indoor shelter.

Cenaida Perez said she smelled smoke from her house in Vacaville early Wednesday morning and ran outside with her 3-year-old daughter, Adriana. She is currently sheltering at a nearby library, but said she was worried about the coronavirus.

“Who isn’t going to be scared of that virus? It has killed so many,” Ms. Perez, 36, said in Spanish. “But also, I don’t want to die like this, burned to death.”

Smoke is making the air unhealthy, and it’s spreading all the way to Nebraska.

The smoke billowing from the wildfires is polluting the air to unhealthy levels, and the scent of smoke is seeping into the skies hundreds of miles away, a sign of just how massive the fires are.

[Are N95 masks helpful for wildfire smoke?]

The air quality in several areas around Northern California grew to dangerous levels this week, particularly in Concord, northeast of Oakland, where the air quality index surpassed 200 on Thursday, marking “very unhealthy” air. The index goes up to 500, but anything above 100 is considered unhealthy. In Gilroy, south of the Bay Area, the index reached above 150 on Friday morning.

The rising smoke, which is easily visible from satellites, is also reaching into neighboring states, and as far away as Nebraska, according to the National Weather Service.

With the smoke and the prospect of a long fire season complicating efforts to control the coronavirus, doctors in Northern California are bracing for an increase in patients.

On a Zoom news conference on Thursday, doctors with the University of California, San Francisco described feeling burned out, but said they were preparing for an increase in their workload. Students, they said, have described feeling as though they are at the center of an apocalypse.

“All of these are a perfect storm of issues,” said Dr. Stephanie Christenson, an assistant professor of medicine at U.C.S.F. who specializes in pulmonary, critical care and allergies.

Dr. Christenson said that although it is too early to definitively say how wildfire smoke affects Covid-19 patients, what is known is that air pollution can inflame the lungs.

As a result, Dr. Christenson said, she’s concerned that wildfire smoke could result in “longer recovery time and even re-hospitalization,” among patients who are recovering from the virus.

For asymptomatic virus patients, the irritation from smoke in the air could irritate them into coughing, she said, which would increase the risk that they transmit the disease.

California’s ‘lightning siege’ has connections to climate change.

A state fire official described it as a “historic lightning siege” — the nearly 11,000 bolts of lightning that struck California over 72 hours this week and ignited 367 wildfires.

Such a flurry of strikes is unusual in California, where it normally takes a full year to tally up 85,000 or so lightning flashes, said Joseph Dwyer, a physicist and lightning researcher at the University of New Hampshire. That is far fewer than Florida, one of the most lightning-prone states, which averages about 1.2 million flashes a year.

Lightning occurs during storms with strong updrafts. During these storms, charged ice particles in clouds collide, generating an electric field. If the field is strong enough, electricity can arc to the ground as lightning, which can ignite dry vegetation: Nationwide, about 15 percent of wildfires start this way.

Strikes across the United States are expected to increase with climate change, as warmer air carries more water vapor, which provides the fuel for strong updraft conditions. A 2014 study estimated that strikes could increase by about 12 percent per 1.8 degree Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) of warming, or by about 50 percent by 2100.

California has been experiencing an intense heat wave this week, and while it is too soon to say precisely how climate change influenced this specific bout of hot weather, “it is likely that there was more lightning because of global warming,” said David M. Romps, a physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, and the lead author of the 2014 study.

“What you could say with certainty is that it was hotter with global warming,” Dr. Romps said. “And certainly the vegetation was drier because of warming. If there were also more lightning strikes, as we would expect, that’s just an additional bump in the direction of more fire.”

Kellen Browning, Nicholas Bogel-Burroughs,Jill Cowan, Henry Fountainand Alan Yuhas contributed reporting.