COVID-19 continues to rage with no end in sight, even as deadlines for insurers to ask for next year’s premium rates arrive. How do insurance companies know what their rates should be?

By Rose Hoban

Even as 2020 doles out one earth-shaking event after another, the insurance companies that can help soften the blows of coronavirus and other health care costs for their members still must try to predict premiums for the coming year.

In these uncertain times, as cases of COVID-19 surge across the nation and North Carolina’s numbers continue their upward creep, a major deadline looms for insurance companies trying to establish rates for 2021.

By the end of July, companies that will offer plans on the Affordable Care Act health insurance marketplace in North Carolina are required to submit proposed rates for 2021 to the state Department of Insurance.

But opposing market forces are pulling proposed premiums in different directions, and predicting what that will look like next year is proving to be a challenging task.

According to their earnings reports, insurance companies could be swimming in dough, or fighting to keep their heads above water as COVID-19 continues to roil health care, along with the rest of the world.

Analysts with the American Academy of Actuaries, professionals who dig into the numbers and trends for insurers and policymakers, expressed uncertainty during a recent webinar about what the coming year would bring.

Insurers will see increased spending on the tens of thousands of Americans who have landed in the hospital because of COVID-19 infections. As a method for comparison Nancy Bennett, a fellow of the AAA, said the average cost for hospitalization for a flu-induced pneumonia in 2018 was $20,000 for admission to a regular bed and $80,000 if a patient required a ventilator.

“[This] provides some sense of the range of possible COVID treatment costs for those who are hospitalized,” she said.

On the other hand, when hospitals were forced to halt elective procedures in March and April to give health care systems time to adapt and prepare for a potential flood of COVID-19 patients, millions of people deferred care or skipped it outright. That could drive down the total claims made to insurance companies in 2020, even as many people continued paying their premiums.

Opposing forces

Tracking data from the Commonwealth Foundation finds the number of visits to ambulatory care practices down by as much as 60 percent during the spring. They remained lower even after practices resumed seeing patients.

“There’s uncertainty up to the net effect on 2020 claims, total costs could be higher or lower than expected,” Bennett explained. “The net effect depends in part on whether deferred services are provided later in 2020, or delayed to 2021 or avoided altogether, which in turn depends on if there’s another wave of the outbreak this year.”

In another presentation, made to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners in April, a different group of actuaries estimated that the claims paid out by insurance companies were down by about 30 percent in March and April.

But by May, rates of infection fell, hospitals gathered enough personal protective equipment to resume non-emergency care and had enough testing capacity to start comfortably admitting those patients. Most hospitals now have elaborate plans in place to create surge capacity for new COVID-19 patients even as they’re continuing to see the knee replacement and the colonoscopy patients that bolster their bottom lines. This means that insurers are now paying out more of the money they take in.

“We’re allowing companies to revise their COVID-19 impact assumptions, up to the latest time possible,” North Carolina insurance commissioner Mike Causey told NC Health News. “As you know, every day we get new data.

“I don’t know if the health insurers have a handle on the entire cost yet. They’re working on it daily as we are, so I believe in a few more weeks, we’ll probably have a better idea of what might happen.”

The question now is whether the costs generated by COVID-19 will offset the savings insurers gained during the period when the number of claims coming in dropped off significantly. In this volatile environment, they try to make their best estimates.

“My message has been clear all along,” Causey said, “we need to hold health insurance cost of premiums down as low as we possibly can.

“A lot of folks are hurting, a lot of people out of work.”

He explained that there are rate filing deadlines throughout the year, with large group plans submitting their premium requests in the fall, and others getting rates approved in the first quarter of the year.

“There’s a lot of uncertainty,” Causey said.

Profitable

There’s no doubt caring for COVID patients will come with an enormous price tag, and ripples from that cost will extend from the federal government, to state governments and through the insurance industry.

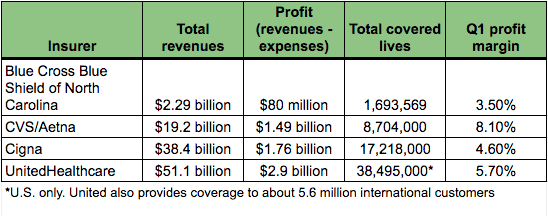

During first-quarter investor calls made in April, just as the scope of the pandemic was becoming evident, most of the large for-profit insurers, such as Aetna, Cigna and UnitedHealthcare, which all have significant footprints in North Carolina, noted their financial positions coming out of the first three months of 2020 was strong.

Cigna reported adjusted revenue of $38.4 billion, CVS Health (which now owns the insurer Aetna) reported revenues increased by 8.3 percent to $66.8 billion and UnitedHealthcare had better than expected earnings on $64.4 billion in revenue.

Once COVID hit, all of these companies say they had planned for setting aside funds to cover providers’ cash flow issues and pay claims more quickly. For-profit payers Aetna, Cigna and UnitedHealthcare all made moves such as waiving copays and coinsurance costs. All three companies also waived prior authorization for hospitalization, which made it easier for their insured patients to be admitted than at a more typical time.

And companies offered discounts on premiums for people who may have been furloughed or laid off their jobs, allowing them to keep their old insurance at a lower cost, at least in the short term.

Insurers also developed contingencies for people who lost their jobs. Some were able to keep their ACA plans, but at a lower cost. Others hopped onto the ACA marketplace during the mid-year, typically a time that insurance would not have been accessible.

All these adjustments cost insurance companies billions, something reflected in their balance sheets.

Large conglomerates such as Aetna don’t just write insurance policies, though. Aetna was purchased in 2018 by CVS. If that company’s insurance portfolios get hammered by the costs of COVID-19, other lines of business, such as pharmacy services and pharmacy benefits management groups, will guarantee a profit. Other large insurers are in the same boat, with diversified companies. For instance, all of the big insurers make billions from managing services for Medicare and Medicaid, which are giant government plans that practically guarantee revenue and profit.

This pandemic has only made the unpredictable more routine. That puts insurance forecasters in a difficult place trying to predict where the next hot spots, such as the current surges in Arizona, Texas, Florida and California, will come and drive up costs to the companies. In many parts of the U.S., these companies could find themselves asking state insurance commissioners for increased premiums for 2021.

Recent earnings reports shed light on the difficulties they’re confronting and how they’re doing thus far.

On July 15, UnitedHealthcare reported its second-quarter adjusted earnings per share was $7.12, and earnings were “substantially higher than anticipated due primarily to the unprecedented, temporary deferral of care in the Company’s risk-based businesses.” Compared to the second quarter of last year, the company’s profit margin doubled, from 5.4 percent in Q2 of 2019 to 10.7 percent in 2020, with $9.2 billion in revenue for the total company.

UnitedHealthcare noted that company revenues increased, in part because the company runs a lucrative pharmacy benefits management plan. UnitedHealthcare also manages the Medicare Advantage and Medicaid policies of millions of public beneficiaries. Even though revenues in the private insurance division of the company were down by $1.1 billion in the second quarter compared to 2019, revenue from those public insurance payers was up by $2 billion. The pharmacy benefits management portfolio earned the company more than $3 billion in revenue.

Other commercial insurers have their Q2 earnings calls in the coming weeks.

NC’s largest not-for-profit insurer

In April, Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina announced it would be foregoing about $600 million in earnings by eliminating cost sharing for COVID testing and allowing plan members to see health care providers for coronavirus illness without prior approvals.

The company also jumped on the telehealth bandwagon. Now many patients can see their providers in a virtual visit and the BCBSNC pays as if the person had visited in person. In the past, telehealth visits were paid at a fraction of the cost for an in-person visit.

The company also extended grace periods for both plan members and employers that were having trouble paying their premiums and sped up reimbursement, which means the company loses money it would have earned in interest payments. Just this month, the company announced discounts on the costs of medications many patients with chronic diseases such as high blood pressure and diabetes take to manage their conditions. BCBSNC has also guaranteed reimbursement to many providers based on last year’s rates instead of renegotiating with providers.

But if revenues take a hit because of a surge in demand for care later in the year, the not-for-profit insurer doesn’t have as much leeway to pad the bottom line with revenue from other lines of business, as the big national commercial players can.

Nonetheless, BCBSNC had a good year in 2019, bringing in just under $9 billion in revenues, for a profit margin of 4 percent. First-quarter earnings in 2020 were also strong, with a margin of about 3.5 percent, according to financial filings provided to NC Health News by the Department of Insurance.

The company took a bath in the early years after the rollout of the Affordable Care Act, losing millions in the individual and small group markets. But since 2015, as the economy boomed and the insurance environment stabilized, those plans have been profitable, according to a review by health care information analysts Mark Farrah Associates.

BCBSNC is the dominant player in North Carolina, with the lion’s share of the market. The company had revenues of $2.2 billion in the first quarter and an income of $80 million. But BCBSNC’s earnings pale next to those of the for-profit health insurance behemoths. CVS/Aetna earned $19.1 billion in Q1 with operating income of more than $1.4 billion or UnitedHealthcare, which earned $51.1 billion in the same financial quarter, with an operating income of $2.9 billion.

Austin Vevurka, then-spokesman for BCBS of North Carolina, had this to say in a June email: “Many experts, including the CDC, are predicting a spike in the fall,” he wrote. “The delay in care may also result in people needing more expensive care.”

The company also might see a revenue decline if the economy continues to be sluggish, with employers and employees unable to pay premiums. That could lead to people dropping coverage, which translates into less revenue for the company, Vevurka added.

COVID’s impact on 2020 claims and service utilization will likely be unknown for some time.

“We have the additional, unexpected $300-plus million expense of fully covering member cost-shares for COVID-19 testing and care,” he said.

BCBSNC, like all insurers, is governed by regulations requiring that 80 to 85 percent of the premiums collected must be spent on medical care. If that doesn’t happen, companies are required to issue rebates, something that was part of federal health reform.

“The vast majority of premiums will either be spent on care or returned via rebate,” he said. The company is slated to pay out $9.6 million in rebates as of the end of the first quarter.

But he declined to speculate what those premiums might be.