As technology evolves, it always creates new moral and ethical problems for us.

Key points:

- Facial recognition technology is being trialled in Australian cities and towns

- A US researcher found that darker-skinned faces were more likely to be misidentified

- IBM has pulled out of the facial recognition business due to concerns about the technology

It means we’ll always need people who’ve been trained to think empathetically, laterally, ethically and historically, to civilise our technology.

Take facial recognition systems.

Should we keep rolling out CCTV cameras with facial recognition technology across Australia’s cities and towns?

On one hand, it helps to catch criminals and prevent crime. There’s no doubt about that. But it represents a huge invasion of privacy and comes with obvious human rights implications.

Where’s the data stored? For how long is it stored? Who has access to it?

What are the chances police will end up using the technology to surveil entire crowds at public protests and create a database of protestors?

And consider the technology behind the technology.

Facial recognition tech in Australia

Police across the globe are turning to a powerful new tool created by an Australian, facial recognition software called Clearview AI. The technology has the potential to alter privacy as we know it.

Read more

In the United States, MIT researcher Joy Buolamwini, recently found most facial recognition technology misidentifies darker-skinned faces, and is far better at correctly identifying the faces of white men.

Such research has prompted Amazon and Microsoft to ban police departments in the US from using their facial recognition technology (for 12 months at least) until the industry is better-regulated.

IBM has decided to pull out of the facial recognition business altogether.

Twenty years ago, we didn’t have to think about these issues. But now the technology exists, we’re forced to.

We’re also beginning to understand how the algorithms that underpin technology like artificial intelligence and facial recognition can reflect the biases of the people who do the coding.

For example, if a tech team with similar backgrounds creates a recruitment program designed to remove human bias from the recruitment process, you can unwittingly get an algorithm that disadvantages women.

Or a team of designers that has never had to think about living with a darker skin tone may develop a soap dispenser that doesn’t recognise black hands.

Or, if you train a self-driving car to identify pedestrians by overwhelmingly showing it images of one race of people, you might end up with a car which doesn’t recognise different skin pigmentations.

To solve these new problems, you don’t just need computer coders, mathematicians and engineers.

You need people who’ve studied ethics, history, politics, and philosophy, and who’ve trained in critical thinking, from across the human spectrum.

Study price increases could jeopardise future workforce

But if the Morrison Government’s proposed changes to Australia’s humanities degrees play out as critics fear, it may become harder to find such people for our future workforce.

Earlier this month, Education Minister Dan Tehan announced plans to increase student fees for humanities courses by 113 per cent, to $14,000 a year, in a deliberate attempt to steer students away from humanities courses that weren’t “job-relevant”.

“We [want to] incentivise students to make more job-relevant choices that lead to more job-ready graduates, by reducing the student contribution in areas of expected employment growth and demand,” Mr Tehan said when announcing the changes.

But tech experts, and academics who help corporations navigate constant changes in technology, including in cyber-security, say humanities graduates are critically important.

Professor Asha Rao, Associate Dean of Mathematical Sciences at RMIT University, teaches the maths behind cryptography — the core of cybersecurity.

Her students have gone on to work for the Big Four banks, Coles and Woolworths, and every major accounting firm in Australia, among other companies.

Professor Rao says the skills learned in humanities courses are crucial in cybersecurity.

“It’s not enough to be able to draw graphs or do what we call penetration testing or hacking or whatever, you are doing risk management,” she told the ABC.

“You need to be able to translate it into the language of risk management.”

Diversity helps ‘weakest link’ in cyber security

At a post-graduate level, Professor Rao said it was not unusual for cybersecurity and analytics schools to accept students with humanities backgrounds because of the benefits that come from having a more diverse classroom.

“We can take people who have not done maths degrees or technical degrees and we can teach them the basic maths and stats they need,” she said.

Cybersecurity, more than almost any other technical field, needed more than just technically minded people, she added.

It required people who understood human nature because humans were “the weakest link” in cyber security.

You can build the most secure system possible but if people don’t understand it, or take it seriously, a system won’t ever be truly secure.

“The technical side is important, but it doesn’t take you anywhere,” Professor Rao said.

“There is no point if you only know how to do it — how you convey what you have done, or what the business needs to do [is what matters].”

Elaine van Bergen, a senior engineering manager at Microsoft, said humanities graduates played important roles in modern tech companies.

She said they were good at identifying potential problems with products before they hit the market, and they were great at selling and explaining products to the public.

‘Evangelists’ crucial for presenting technology

The role of a “tech evangelist”, who presents new technology to large and small audiences, requires a very different set of skills to a coder, she said.

“I have several friends who were really good at that, and they didn’t study technology at university — they were theatre majors,” Ms van Bergen told the ABC.

“I don’t see why their job path would be any less job ready than my path.”

Ms van Bergen said an area in which humanities grads excelled was in “requirements gathering”, which involves researching and discovering the requirements of a product from users and other stakeholders.

It’s an important part of the product-development process. They might use interviews, workshops, brainstorming, and role-playing to discover what customers really want or need from a product.

“That’s typically people that come in with humanities kind of backgrounds and/or tech,” she told the ABC.

She said Microsoft was conscious of the benefits of a diverse workforce because of the nature of technology and the role it plays in society, so it had overhauled its hiring practices.

“It includes everything from removing the need for degrees in a lot of our job ads, making sure that we only put the skills that are absolutely required, because otherwise people don’t apply if they don’t match all the skills,” she said.

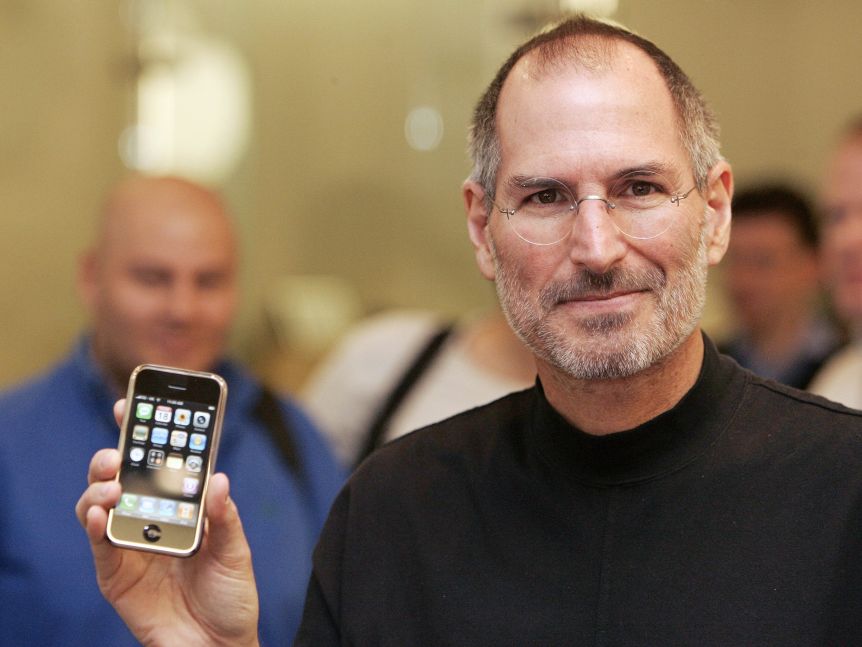

Steve Jobs used calligraphy when designing first Mac

He said one of the best things he ever did was drop out of formal classes at college and take a calligraphy class.

“I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great,” he said.

“It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture, and I found it fascinating.

“And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography.

“If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts. And since Windows just copied the Mac, it’s likely that no personal computer would have them.

“Of course, it was impossible to connect the dots looking forward when I was in college. But it was very, very clear looking backward 10 years later.”