with Paulina Firozi

This time, as the nation erupts over the latest example of police violence toward African Americans, there’s a pandemic in the background.

The confluence of massive protests and a pandemic provides an unprecedented and tangible example of the steep challenges black people face every day in the United States.

By nearly every benchmark, the coronavirus outbreak has produced more severe consequences in the lives of African Americans compared with their white counterparts. Black Americans are infected with the virus at higher rates and dying of it more frequently. They are more likely to have lost their employment because of the shutdowns. And they started out with fewer resources on hand to weather the health crisis.

“It became really clear covid was not a leveler,” said Steven Brown, a research associate at the Urban Institute and author of an analysis on how the virus has affected the economic well-being of minorities. “Even though we’re all at risk, it was incredibly clear that some people were more at risk.”

Demonstrators confront law enforcement during a protest on June 1 in downtown Washington, DC. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images) ***BESTPIX***

For nearly a week, people protesting George Floyd’s death have held nightly demonstrations in a number of U.S. cities, some of them marching peacefully even as others vandalize stores, government buildings and cars. As protests intensified yesterday in New York, Chicago and St. Louis, President Trump threatened to deploy federal troops if state and city leaders don’t act to quell the chaos.

The protests are stoking concerns that black Americans gathering in close proximity could further worsen disparities that have been years in the making. These disparities are now getting unprecedented attention because of two of the biggest news events this year: the pandemic and Floyd’s death.

Just as the protests over Floyd’s death have brought fresh attention to how black Americans are treated by law enforcement, the pandemic also stirred up a focus on how they lag far behind when it comes to personal health and access to affordable, high-quality care.

“The stories about protests are also the stories about covid-19 and racism,” said Zinzi Bailey, a social epidemiologist at the University of Miami.

Protesters march in New York City during a solidarity rally for George Floyd on Saturday. (Wong Maye-E/AP)

African Americans have higher coronavirus infection rates.

One reason for this is they tend to live in cities, where the virus has taken hold more aggressively than in suburban or rural areas. U.S. localities with larger-than-average black populations account for more than half of coronavirus cases, according to a national study by Amfar, the Foundation for AIDs Research.

“The Amfar study, based on data collected April 13, focused on counties in which black people made up more than 13 percent of the population,” my colleague Vanessa Williams wrote last month. “Disproportionately black counties account for 22 percent of all U.S. counties but have been home to 52 percent of coronavirus cases and 58 percent of deaths from covid-19.”

Black Americans are dying from covid-19, the disease the virus causes, at a rate nearly two times higher than white Americans.

While African Americans comprise 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 24 percent of deaths where race is known, according to the Covid Tracking Project.

Chronic health conditions including hypertension and diabetes — which significantly increase a person’s risk for serious covid-19 complications — are a major factor here.

In Washington, D.C., for example, a majority of confirmed cases are in some of the city’s densest neighborhoods with large majority-minority populations and high rates of chronic health conditions, my colleagues Aaron Williams and Adrian Blanco reported.

“Wards 5, 7 and 8, which flank the eastern edge of the city, are majority-black areas and have above national rates of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, obesity and heart disease,” they wrote. “These are also the wards with some of the highest-known case counts of the virus, according to city health data.”

In Louisiana, another area hit hard by the virus, the state’s health department estimated that black Americans account for 55 percent of all deaths. Almost 60 percent of residents who died had hypertension and 37 percent had diabetes, my colleagues reported.

Larger shares of African Americans lost jobs, work hours or income during the lockdowns.

Black people, as well as Hispanics, tend to have jobs impossible to do at home, like working in grocery stores or warehouses or as caregivers in hospitals or nursing facilities. Just 35.4 percent of black adults reported in an Urban Institute survey that they can do part of their work remotely, compared with 43.4 percent of white adults.

And while many black people work in jobs considered “essential,” black families reported financial losses during the March and April lockdowns at a slightly higher rate. Forty-one percent of blacks said their families experienced a loss of a job, work hours or job-related income, compared with 38 percent of whites.

And in the event of job loss, African American families tend to have fewer savings to draw upon. More than half of black adults with pandemic-related income losses reported drawing on savings or running up credit card balances, compared with 36 percent of whites.

More black Americans are struggling to pay for housing.

Black Americans were more likely to miss their May housing payments than their white counterparts, according to U.S. Census Bureau data analyzed by the Urban Institute.

About a quarter of black renters said they didn’t pay their rent last month, compared with 14 percent of white renters. The differences were more pronounced among those who own homes; 28 percent of black homeowners didn’t pay their mortgage, compared with just 9 percent of white homeowners.

And black people reported slight or no confidence in their ability to make their housing payments at a rate nearly double that of white people.

Ahh, oof and ouch

AHH: Americans are delaying medical care amid the pandemic. Doctors and hospitals can’t afford the losses.

Hospital visits have been declining nationwide. By the middle of May, almost 94 million American adults had delayed medical care because of the pandemic, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. About 66 million of those people needed care unrelated to the virus but did not get it, Ted Mellnik, Laris Karklis and Andrew Ba Tran report.

“As in many other industries, those lost visits represented a widespread financial crisis for hospitals and other health-care providers, even in places the novel coronavirus hardly touched,” they write. “ … Many of the nation’s hospitals can ill afford theses losses. A third were already losing money on patient care before the virus hit, according to data compiled by Definitive Healthcare. More than 1,200 hospitals operated in the red in two or more of the last five years. Then the coronavirus hit with a one-two punch. Patient revenue dried up, and preparing for possible outbreaks drove up costs.”

Hospitals have started to reschedule surgeries and reopen clinics, particularly in regions that never saw surges in coronavirus cases, or in places where cases are declining.

“In the latest smartphone data from the location tracking company SafeGraph, hospital visits started to recover in the first half of May, although they were still down from 2019 by about 40 percent,” they add.

OOF: Experts are disputing reports that the coronavirus is becoming less lethal.

A top doctor in northern Italy said patients in his hospital have been emerging with lower levels of the virus compared with two months ago — remarks that drew swift pushback, Joel Achenbach, Ariana Eunjung Cha, Ben Guarino and Chelsea Janes report.

Paolo Bonacina, 56, of the northern Italian city of Bergamo, receives a farewell from intensive care nurses after recovering from covid-19. (Ina Fassbender/AFP/Getty Images)

Alberto Zangrillo, head of San Raffaele Hospital in Milan, shook the global public health community when he told a national TV station over the weekend that the “virus clinically no longer exists in Italy.” In a follow-up interview with The Washington Post, he suggested something different may be happening “in the interaction between the virus and the human airway receptors.”

Top WHO official Michael Ryan said at a news conference that “we need to be exceptionally careful not to create a sense that all of a sudden the virus by its own volition has now decided to be less pathogenic. That is not the case at all.”

“The consensus among other experts interviewed Monday is that the clinical findings in Italy likely do not reflect any change in the virus itself,” Joel, Ariana, Ben and Chelsea report. “Zangrillo’s clinical observations are more likely a reflection of the fact that with the peak of the outbreak long past, there is less virus in circulation, and people may be less likely to be exposed to high doses of it. In addition, only severely sick people were likely to be tested early on, compared with the situation now when even those with mild symptoms are more likely to get swabbed, experts said.”

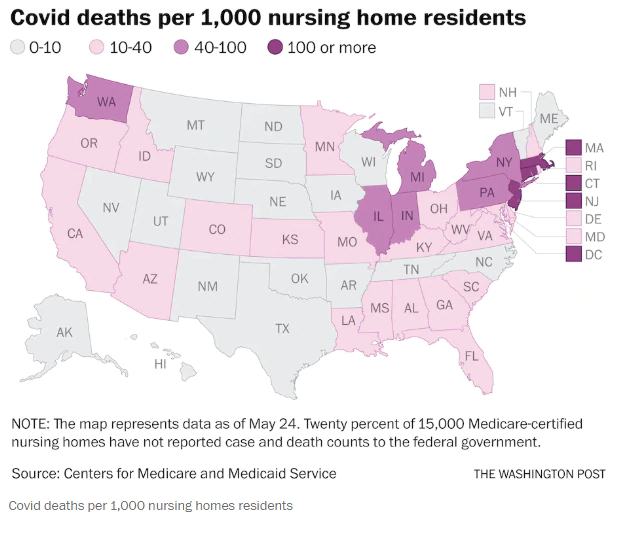

OUCH: More than 25,000 nursing home residents have died during the pandemic.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services detailed the first national account of fatalities in the 15,000 nursing homes that receive Medicare and Medicaid funding. The government report found 60,000 were infected as the coronavirus swept through the nation’s long-term care facilities.

Nursing homes with a history of low marks for patient care and staffing have been particularly impacted, Debbie Cenziper, Peter Whoriskey and Joel Jacobs report.

The actual number of nursing home illnesses and deaths could be higher.

“Only about 80 percent of the nation’s nursing homes reported data to the federal government, and they were required only to include cases since early May,” they add.

According to a Post account of nursing home cases and deaths, based on state reports, more than 28,000 residents have died.

“On Monday, [CMS Administrator Seema Verma] focused heavily on infection control, saying the agency would strengthen enforcement, including civil penalties, of nursing homes with persistent violations of federal standards meant to prevent the spread of illness,” Peter, Debbie and Joel report. “…Verma said the agency will distribute $80 million to states to increase infection-control inspections of nursing homes during the pandemic. States that fail to inspect all Medicare-certified homes by July 31 will be required to submit a corrective plan to the federal government. Those still lagging by August will lose some of the money.”

Even amid the fear, risk and isolation, residents in some homes are still finding ways to connect.

Residents in nursing homes, assisted-living facilities and retirement communities across the country are quarantined because of the coronavirus that has impacted the elderly more than anyone else. But they’re not always completely alone, Marc Fisher reports in this uplifting piece.

“On Radio Recliner, a new online radio station, the DJs are elderly folks who have spent the past two months stuck in their rooms, meals delivered to their doors, activities canceled, their relatives relegated to waving through a window, at best,” he writes. “At a time of great fear and risk — old-age home residents make up about 40 percent of the nation’s deaths from the virus — the disc jockeys get to tell stories of better times as they spin their favorite tunes, from Elvis and ’40s big band tunes to ’60s rock (including the hard stuff) and a whole lot of love songs.”

Industry efforts

Eli Lilly said it started an early-stage trial of a potential covid-19 treatment.

The drugmaker is conducting the first study in the world of an antibody treatment against the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. It was derived from a blood sample from one of the first patients in the United States to recover from the illness, Reuters’s Ankur Banerjee reports.

The Eli Lilly corporate headquarters in Indianapolis. (Darron Cummings/AP)

“Lilly said its early stage study will assess safety and tolerability in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and results are anticipated by the end of June,” Ankur reports. “ … Lilly said it expects to move into the next phase of testing, studying the potential treatment in non-hospitalized COVID-19 patients, if the drug is shown to be safe.”

Gilead Sciences said remdesivir has helped some patients with moderate covid-19 cases.

New data from a study the company conducted found the drug benefited patients with “moderate” covid-19 when they received the treatment for five days, though there was not a statistically significant benefit when the treatment was administered for 10 days, Stat News’s Matthew Herper reports.

The Gilead Sciences headquarters in Foster City, Calif. (Ben Margot/AP)

These “moderate”-case patients were hospitalized but did not require mechanical ventilation.

The new data “add to the evidence that the medicine is at least somewhat effective treatment for Covid-19. But they will also likely add to the debate of exactly how effective the remdesivir is, and in what patients,” Matthew adds. “ … An earlier study showed that patients with severe disease who received remdesivir recovered four days faster than similar patients who received placebo.”

Moving toward a new normal

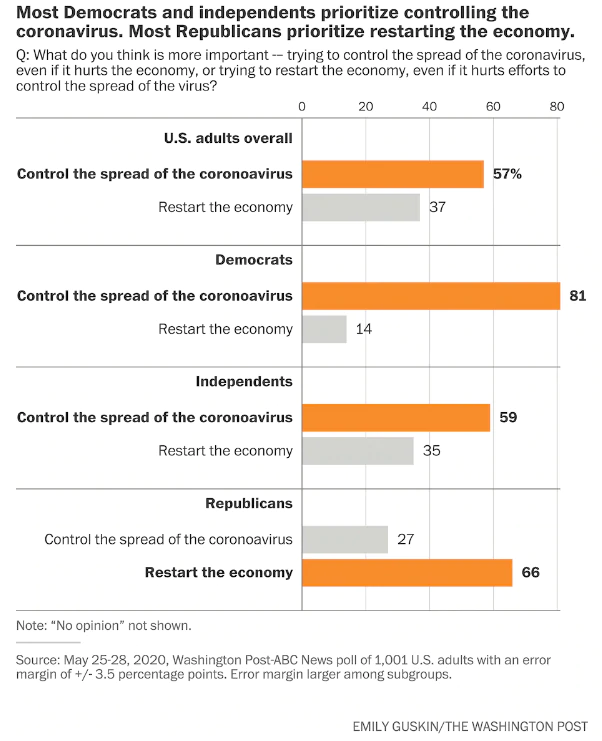

Most Americans still favor curbing the spread of the coronavirus over reopening the economy.

Nearly 6 in 10 Americans say trying to control the spread is more important, even if it hurts the economy, a new Washington Post-ABC News poll has found.

The poll found 81 percent of Democrats say the same, as do 27 percent of Republicans. Meanwhile, 66 percent of Republicans say reopening the economy is more important, even if it hurts the effort to control the spread of the virus, Scott Clement and Dan Balz reports.

“Americans are nearly as divided along partisan lines when asked whether they are willing to go to stores, restaurants and other public places ‘the way you did before the coronavirus outbreak,’ ” they add. “Two-thirds of Republicans say they are willing to resume such activities, compared with 4 in 10 independents and fewer than 2 in 10 Democrats. Overall, 58 percent of Americans say it is ‘too early’ to go to stores, restaurants and other public places the way they did before.”

Around the world

A new Ebola outbreak has been declared in Congo’s Équateur province.

The province’s governor said on national radio there were five likely cases, and four of the infected had died, Max Bearak reports. The cases were found in Mbandaka, the capital of Équateur province, which last saw an outbreak of the deadly virus in 2018.

Mbandaka, an important port city at the confluence of the Congo and Ruki Rivers, last recorded a case of Ebola in 2018. (Junior D. Kannah/AFP/Getty Images)

“Congo has grappled for almost two years with a separate Ebola outbreak in its northeastern provinces that has killed 2,272 people so far,” he adds. “In April, that outbreak, the country’s worst, had been just days away from being declared over when new cases were found. The same region is also home to the world’s largest ongoing measles outbreak.”

The Ebola virus, which is endemic to Africa’s tropical rainforests, is unrelated to the novel coronavirus. There have been more than 3,000 coronavirus cases in Congo, though none confirmed in Mbandaka.

Coronavirus latest

A few more stories to catch up on this morning:

Consequences of the pandemic:

- The fallout from the pandemic will cost the U.S. economy about $8 trillion through 2030, per new projections released by the Congressional Budget Office, Jeff Stein reports.

Congress on coronavirus:

- Senate Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) called on Congress to “act with a fierce sense of urgency” to pass another round of coronavirus relief legislation in response to the CBO’s estimate.

- Members of Congress planned to unveil a bipartisan measure to regulate contact-tracing and exposure-notification apps to make sure the technology meant to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus don’t impact users’ privacy, Tony Romm reports.

Industry impact:

- Zoloft, one of the nation’s most widely prescribed antidepressants, is in short supply. The shortage is a result of surging demands as the pandemic continues to take a toll on people’s mental health, Bloomberg News’s Anna Edney reports.

Good to know:

- Spain announced zero new coronavirus-related deaths in a 24-hour period for the first time since March, the Associated Press reports.

The new normal:

- Parents and teachers are getting creative as they find new ways to get kids to wear masks, Hannah Natanson reports.