The ways Americans capture and share records of racist violence and police misconduct keep changing, but the pain of the underlying injustices they chronicle remains a stubborn constant.

Driving the news: After George Floyd’s death at the hands of Minneapolis police sparked wide protests, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz said, “Thank God a young person had a camera to video it.”

Why it matters: From news photography to TV broadcasts to camcorders to smartphones, improvements in the technology of witness over the past century mean we’re more instantly and viscerally aware of each new injustice.

- But unless our growing power to collect and distribute evidence of injustice can drive actual social change, the awareness these technologies provide just ends up fueling frustration and despair.

For decades, still news photography was the primary channel through which the public became aware of incidents of racial injustice.

- A horrific 1930 photo of the lynching of J. Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith, two black men in Marion, Indiana, brought the incident to national attention and inspired the song “Strange Fruit.” But the killers were never brought to justice.

- Photos of the mutilated body of Emmett Till catalyzed a nationwide reaction to his 1955 lynching in Mississippi.

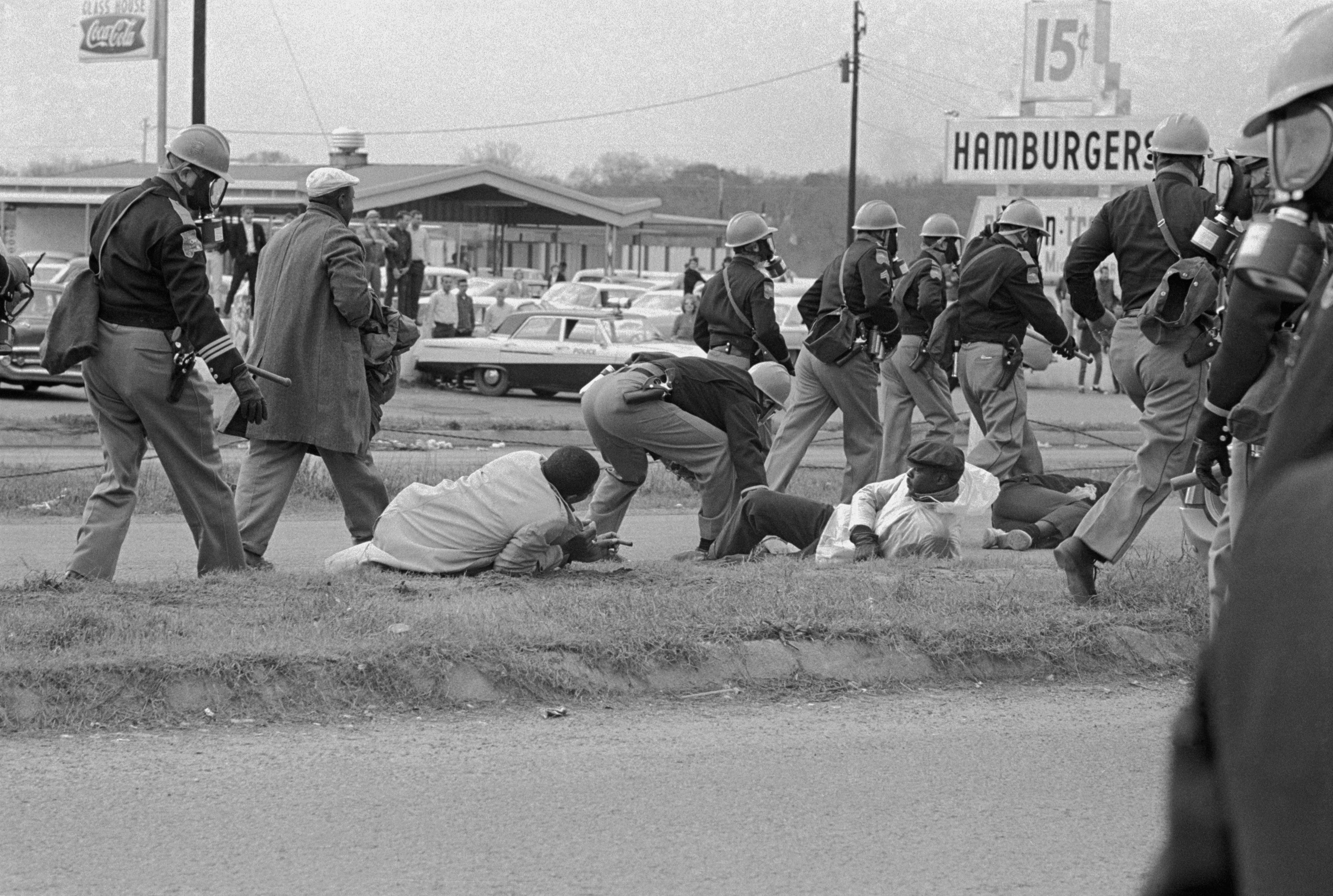

In the 1960s, television news footage brought scenes of police turning dogs and water cannons on peaceful civil rights protesters in Birmingham and Selma, Alabama into viewers’ living rooms.

- The TV coverage was moving in both senses of the word.

In 1991, a camcorder tape shot by a Los Angeles plumber named George Holliday captured images of cops brutally beating Rodney King.

- In the pre-internet era, it was only after the King tape was broadcast on TV that Americans could see it for themselves.

Over the past decade, smartphones have enabled witnesses and protesters to capture and distribute photos and videos of injustice quickly — sometimes, as it’s happening.

- This power helped catalyze the Black Lives Matter movement beginning in 2013 and has played a growing role in broader public awareness of police brutality.

Between the lines: For a brief moment mid-decade, some hoped that the combination of a public well-supplied with video recording devices and requirements that police wear bodycams would introduce a new level of accountability to law enforcement.

The bottom line: Smartphones and social media deliver direct accounts of grief- and rage-inducing stories.

- But they can’t provide any context or larger sense of how many other incidents aren’t being reported.

- And they don’t offer any guidance for how to channel the anger these reports stoke — or how to stop the next incident from happening.