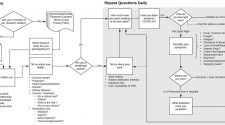

Medical staff at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Pa., say the institution has struggled to protect them and their patients during the chaotic early days of the coronavirus crisis. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

The nurse was pregnant — and worried. But in mid-March, early in the covid-19 crisis, a manager at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Pa., assured her she would not be sent to the floor for patients infected with the deadly virus. The risks for expectant mothers were too uncertain.

Two days later, she says, the administration changed course, saying the hospital needed “all hands on deck.” The pregnant nurse said she was sent back and forth between the “covid floor” and the neonatal intensive care unit, known as the NICU, where she normally treated vulnerable newborns and recovering mothers.

It wasn’t just her baby she was worried about, she said, but the immunocompromised newborns and mothers who she was treating without informing them that she was also working on the covid floor. Even as she cared for patients symptomatic of covid-19, administrators provided her with crucial protective gear only after tests came back positive, usually several days after she first attended to the infected patients.

The nurse was one of 11 medical staff and union representatives who described from the inside how a hospital in a small Pennsylvania city struggled to protect medical staff and patients during the chaotic early days of the crisis. Seven of the nurses, who work at two sister hospitals in Scranton, spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of reprisals by the Tennessee-based company that owns their hospitals, Community Health Systems.

Like many hospitals across the country, Moses Taylor wasn’t prepared for the influx of highly contagious patients in the absence of vast quantities of protective gear. But measures taken by CHS to cope with the crisis stand out. The shortage led administrators to initially order staff to work with suspected covid-19 patients without adequate protection and to shuttle back and forth between floors where they feared they would infect cancer patients and babies, nurses say.

Staff interviewed by The Washington Post said that they were speaking up out of concern for what they see as a perilous situation and out of anger over the disorganization, carelessness and greed that they say flows from a distant corporate owner.

Two of the nurses working at Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton, Penn., say that they don’t have enough personal protective equipment as they care for patients both with and without covid-19. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

The nurses and representatives of their union said that many of their safety concerns were dismissed as recently as last Friday, April 3, during a meeting with the hospital administration. But on Tuesday, after CHS was contacted by The Post, the hospital announced several changes in policy to prevent the spread of infection.

The hospital’s chief executive, Michael Brown, said in a statement that covid-19 has been an unprecedented challenge that required frequent changes and that the hospital is following guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“None of us has experienced a health crisis of this magnitude before,” he said. “We are adjusting and improving our response every day, and I am incredibly proud of all of the ways our physicians, nurses and team members are working together to care for our patients and each other.”

Matthew Yarnell, the president of Service Employees International Union Healthcare PA, the state’s largest union of nurses and health workers, welcomed the changes announced this week, which include designating an employee entrance to the building and screening staff members for fevers before entering and leaving the 214-bed hospital.

But he added in a statement: “It shouldn’t take attention from a national media outlet to move CHS to put the safety of patients and frontline caregivers first.”

The hospital said in a statement that it had implemented temperature checks on April 4, but a memo to staff this week obtained by The Post says they went into effect April 8.

With 99 hospitals in 17 states, CHS is one of the largest for-profit health companies in the U.S. But through spinoffs, sales and closures, the number of hospitals in the chain has fallen from over 200 in 2014. CHS has been facing sizable debt, and its share price has more than halved since the pandemic began to take hold in February.

“Over the past few years, we have made significant progress in our operational and financial performance, putting the company back on a positive trajectory with future growth potential,” Tomi Galin, the head of corporate communications for CHS, said in an email. “Since 2016, we have been divesting hospitals to pay down debt and also to create a stronger core portfolio for the future.”

The years have been good for CHS chief executive Wayne Smith, whose total compensation has ballooned in recent years to $8 million, including stock awards and incentives, according to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

After being contacted by The Post for comment on this story, the company filed a document to the SEC stating that Smith was voluntarily taking a 25 percent cut to his base salary, which was $1.6 million last year, and that other executives were taking a 10 percent cut. The company said in a statement that the pay cuts would help pay for a $3 million fund for employees “suffering hardships.”

Community Health Systems owns six hospitals in Pennsylvania, including the Moses Taylor Hospital in Scranton. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

CHS owns six hospitals in Pennsylvania. In interviews, workers in other CHS hospitals also reported problems over the lack of protective gear and inconsistent policies since covid-19 patients began to be admitted.

Union officials representing the nurses say that they had repeatedly tried to raise their concerns about the dangers to their members and patients but had been mostly rebuffed until this week.

“Anything you say, anything about the coronavirus or that we don’t have enough equipment at the hospital, they’re pulling you into the office,” says Dan Coviello, who works as a surgical tech at a sister CHS hospital in Scranton and is the president of the SEIU PA chapter that represents nurses at that hospital.

Brown, the chief executive, says the company urges employees to speak up about safety concerns and says that they can make anonymous complaints about retaliation to a hotline.

“Our organization does not support or condone retaliation and will address it immediately if such behavior is found to have occurred,” he said.

But Coviello says that employees at the two CHS hospitals in Scranton who have raised concerns about unprotected contact with specific covid-19 patients have been threatened with termination for violating health privacy laws. When he has gone to management with safety complaints from members at his hospital, he says the first question is “What’s the person’s name?” which he says reflects their primary interest in rooting out complainers.

Timothy Landers, a professor of nursing at Ohio State University, says that this kind of pressure on nurses, especially during a health-care crisis, can harm patients.

“If you have nurses who are kind of overworked, overstressed, feeling underappreciated, put upon, not respected or protected by management, then you see all kinds of bad things happen with patient care,” he said.

Galin, the CHS spokeswoman, said in a statement that the company is working around-the-clock to resupply its hospitals with protective equipment.

“First and foremost, we recognize that protecting our caregivers is critically important, and we are doing everything possible to create the safest work environments possible,” she said in an email.

Nevertheless, the union and nurses say those who speak out about problems have been hauled in for disciplinary meetings, had their shift hours cut, or had their schedules changed.

“In the last week, we have members being pulled in to managers’ offices and they’re giving them coaching because they’re speaking out and they want them to be quiet,” Coviello said of his hospital, Regional Hospital of Scranton. “And some got written discipline. And in those disciplines, which I’ve been in, they said that if they continue to speak out, there will be further discipline up to being fired from the hospital.”

A sign indicates where patients getting tested for covid-19 should enter Moses Taylor Hospital. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

A second nurse who works in the neonatal intensive care unit said that fear of retaliation is the reason she could not speak publicly. “That’s why I’ve been so adamant about being anonymous,” she said, “because it’s ugly.”

She and others said say they are losing the very thing that made them want to be nurses — the chance to help the sick and infirm. They say that tensions with management and hospital policies have put them in the impossible situation of endangering the lives of their patients.

“It feels like these guys are loading a gun,” the nurse said. “But we’re the ones who have to pull the trigger.”

When it came to questions about whether pregnant nurses could be removed from duties on the covid floor, one nurse says the hospital’s chief medical officer told her, “Absolutely not.”

“Then it would be only males and postmenopausal women taking care of these patients,” she recalled him saying.

The hospital said in a statement that the allegation took the officer’s comments out of context.

“What he was saying is that the CDC can give no direction at this time regarding pregnant healthcare workers and ‘without CDC guidance, I can’t ask only male and post-menopausal women to care for COVID-19 patients,’” the emailed statement said.

Landers said that there have not been definitive studies on the health risks for pregnant nurses, but he added that hospitals should defer to nurses’ concerns and redeploy them if they are worried about their safety.

Moses Taylor is an acute care hospital with 400 doctors that is best known for its pediatric and neonatal care. With more than 2,500 births last year — an average of 48 a week — nurses were worried about how to deliver babies without infecting their mothers.

As they watched the coronavirus march across the globe months ago, the nurses said they got no guidance and saw no planning from administrators on how it would cope when coronavirus arrived at the hospital’s threshold. Their anxiety was compounded by past experience: Even before this crisis, they said, Moses Taylor was constantly scrimping on supplies and shifts to cover busy wards.

The only sign they saw that the hospital was preparing was when managers began locking away in administrative offices the critical N95 masks and gear that can prevent infection. When one nurse asked a manager what they planned to do if any medical staff were infected, she said she was told: “Well we’ll figure that out when that time comes.”

Brown, the chief executive, disputes that charge, saying that the hospital is being transparent with staff about the covid-19 cases, the supply of protective gear, staffing and “other things that matter to them, because we believe that they need to know what’s happening across the hospital.” Moses Taylor said as of April 8 it was caring for seven patients confirmed to have covid-19 and five patients whose test results were still pending.

Two of the nurses have not spoken publicly about their working conditions in fear of retaliation from their supervisors and hospital management. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

In early March, as the first patients began to arrive, staff say they got different directives every day from their managers on how to protect themselves and patients. Then late last month, a nurse working on a floor that housed the oncology and orthopedic departments ran into the hospital’s chief medical officer, who had news.

“We’d lost the coin toss between us and another floor,” the nurse said. “We were now going to be the covid floor.”

They immediately began staffing the floor with some full-time nurses, while alternating others between departments. Some nurses were going directly from treating covid patients to administering chemotherapy to cancer patients, who would be especially endangered by a covid-19 infection.

The nurse on the orthopedic and oncology floor complained to a supervisor about the risks at the beginning of her shift. The manager told her she would look into the issue and provide guidance at the end of the day — after the nurse would have already treated several cancer patients. She never heard back from the supervisor. “It goes in one ear and out the other,” she said.

Even when the nurses have secured access to protective gear, they said, it has been extremely limited. They were expected to wear one-use masks for five shifts. Some were told to disinfect the masks in between uses with rubbing alcohol that gave them headaches when they put them back on. Others were told to use one mask each time they treated a specific patient and to put it in a paper bag until the next time — a practice that could allow virus particles to migrate, potentially infecting them. They witnessed staff coming out from treating virus patients in protective gowns and then sitting on chairs in the hallway without taking them off.

The hospital says it is following CDC guidance on the use and reuse of protective masks and sent a link to the recommendations, which specifically refer to using paper bags for N95 storage. However, the same recommendations rule out the reuse of masks in such circumstances without sterilization.

“Discard N95 respirators following close contact with any patient co-infected with an infectious disease requiring contact precautions,” the recommendations say. Covid-19 is such an infectious disease, Landers, the Ohio State professor, said.

“That would not be an example of good practice,” he said of Moses Taylor.

The hospital says that since mid-March medical staff has been told to report symptoms, but nurses say managers ignored symptoms they reported on more than one occasion. (Elizabeth Herman/For The Washington Post)

According to the nurses, the protective masks were only being given out for treating confirmed covid-19 patients. But nurses are often expected to walk into rooms without knowing a patient’s condition.

“They just tell us, you know, go check on and see so-and-so,” one nurse explained. “You have absolutely no idea what you are walking into. No idea why this person is in the hospital. No idea what they have. Nothing.”

The hospital says that since mid-March medical staff has been told to report symptoms, but nurses say managers ignored symptoms they reported on more than one occasion.

In one instance, a nurse with a newborn and a young daughter at home who had been out sick for two days with a fever and a cough reported for duty and asked whether she should get to work, according to two nurses she spoke with. The nurse’s supervisor sent her to human resources. Human resources sent her back to her supervisor, who then took her temperature.

Despite having taken an ibuprofen, she still had a low-grade fever. The supervisor said, “‘Well I’m not worried about it. Just clock it,’” one nurse recounted.

The problems were extensive. One of the NICU nurses said staff had been asking for weeks what they would do if an expectant mother came in with signs of infection. They were given no answer. And then late last month it happened.

“It was literally chaos. Nobody knew what was going on. We had to fight to get N95 masks to take care of this mother,” she recalled.

Then they couldn’t figure out where to take the baby for quarantine. The administration wanted to send the newborn to the pediatric unit, where there was a risk of older children passing on the flu or other illnesses.

Only days after this incident did the hospital offer a written plan for such circumstances, she said.

The hospital says that no newborn or new mother has tested positive following hospital care.

The nurses’ allegations come as hospitals across the country are facing test and mask shortages and a torrent of infections that is stretching their capacity. Concerns similar to those raised by the Moses Taylor medical staff were recently highlighted by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’s internal watchdog in a survey of hundreds of hospitals.

“This place actually makes you second-guess your career choice,” one nurse lamented. “As much as I love my job, it’s like, is it even worth it being a nurse and putting these patients at risk? I mean, that’s the biggest concern, you know, at the end of the day, did I give my best care possible? And this place prevents you from doing that.”

Union officials and hospital staff finally met with hospital administrators last Friday, after weeks of complaints about safety. But staff say they got little information. When they asked how many masks the hospital had and how it was distributing them, they were told that the hospital had adequate supplies and would follow guidelines from the CDC.

When they asked for clarity on what employees should do if they came down with covid-19 symptoms, they were told that they were relying on staff to consult their own physicians and to “self-screen.” The hospital would not test staff.

“Self-screening for covid?” one union official asked, incredulous. “Are you kidding me?”

On Wednesday, the hospital began screening the staff.