In the fraught months and years after the 9/11 attacks and the anthrax cases that followed, federal and state health officials began planning for the unthinkable — a disease outbreak that could affect millions and strain health care systems to the limit.

Now health officials say that same planning has New Hampshire well-positioned to handle an outbreak of the coronavirus that has sickened tens of thousands of people and killed more than 2,200, the overwhelming majority of them in China.

Experts stress that the exposure risk to Granite Staters remains very low. While 12 New Hampshire residents have already died of influenza this season, no cases have been reported here of the coronavirus illness that international health agencies now call COVID-19. Three people were tested for the virus after returning to the state from China earlier this year, but none tested positive.

“Overall, the risk to the general public is low,” said Elizabeth Daly, chief of the Bureau of Infectious Disease Control at the state Department of Health and Human Services. “You have to have come into contact with someone who is a confirmed case of novel coronavirus in order to get this virus.”

“Influenza is a much bigger risk to people right now,” Daly said. In addition to deaths linked directly to flu, she said, “Each week, somewhere around 5% to 10% of people who die in New Hampshire are dying from pneumonia, which is often related to flu.”

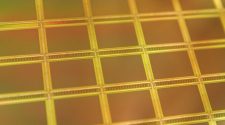

This is the CDC’s laboratory test kit for the novel coronavirus. The CDC is shipping the test kits to laboratories it has designated as qualified, including state and local public health laboratories, Department of Defense laboratories and select international laboratories.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, as of Friday 35 confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported in the United States, including 18 passengers from the Diamond Princess cruise ship who recently returned to the U.S. on State Department-chartered flights.

The CDC is developing test kits to send out to public health labs so states can test patients locally, Daly said. She expects those will be available in New Hampshire “within a few weeks.”

All 26 acute-care hospitals in New Hampshire, from the largest to the smallest, have the ability to handle potential COVID-19 patients, Daly said, though some facilities might choose to transfer patients if they don’t have the staffing to follow strict containment and treatment protocols.

Kathy Bizarro-Thunberg, executive vice president of the New Hampshire Hospital Association, said hospital clinicians and executives have been working closely with the CDC, DHHS and other agencies to stay updated on the new coronavirus illness. The recommendation now is for all health care providers to ask patients who show up with respiratory symptoms about international travel, she said.

Hospitals in the state are already stretched thin because of workforce shortages, Bizarro-Thunberg said, but plans are in place for hospitals to share resources if a public health threat were to arise. “No one’s going to be working alone if they are overwhelmed; there are going to be opportunities to share the workload,” she said.

When it comes to emergency preparedness, hospitals are cooperating rather than competing, she said. “New Hampshire’s a small state. We need to all rally around each other because we all support the health care of our communities,” she said.

Daly, who is also director of public health preparedness at DHHS, said that after the 2001 terrorist attacks, the federal government provided funding to states to ramp up preparedness for public health emergencies.

New Hampshire, along with the CDC and other states, created a Health Alert Network (HAN), a system for communicating information about public health threats to more than 14,000 providers here, including physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, schools, emergency medical services and others.

Elizabeth Daly

chief of Bureau of Infectious Disease Control .

The state conducts regular exercises and drills to test preparedness plans — for example, how vaccines and antibiotics would be channeled from federal agencies to New Hampshire providers. The system already has been tested, officials said, during outbreaks of the H1N1 flu virus in 2009-10 and the SARS virus in 2003.

Daly said community interest about COVID-19 has been high. The department has fielded numerous calls from providers as well as from school officials concerned about the impact on international students. The state also has activated its incident management team, which meets three times a week to monitor developments.

“So while we haven’t had a case here in New Hampshire, … there has been substantial activity here at the department, making sure we’re prepared and responding to what’s been happening globally,” Daly said. “If we were to have a case, hopefully that person will have been appropriately identified and isolated out in the community.”

Dr. Michael Calderwood, an infectious disease physician and hospital epidemiologist, is associate chief quality officer at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and an associate professor at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine. He’s also a member of DHMC’s “high-threat infection team,” a specialized, 40-member medical team trained to diagnose and care for patients with infectious diseases such as SARS and COVID-19.

Dr. Michael Calderwood

infectious disease physician and epidemiologist

That team was activated a few weeks ago for a suspected case of COVID-19, one of the three New Hampshire patients whom the CDC tested and found negative, Calderwood said.

All patients coming in to outpatient clinics, the emergency department or the hospital are now being screened for symptoms and travel history, he said.

“If it turns out they have risk factors for COVID-19, we can work with that clinic to get them to the right location where we have a special team that will help to care for and diagnose an individual patient,” he said.

For perspective, Calderwood said, seven coronaviruses are known to cause human disease, he said, and “four of those are responsible for 10% to 30% of common colds worldwide.”

The other three can be more deadly, he said. SARS sickened 8,000 people in 2002-03, with a 10% fatality rate; MERS has caused about 2,500 cases to date, mostly in Saudi Arabia, with a 34% fatality rate; and the new virus is causing COVID-19.

Nearly 99% of cases of COVID-19 have been in mainland China, Calderwood said. While the fatality rate in China’s Hubei Province, where the outbreak began, has been around 18%, outside of China that number appears to be closer to 1%, he said.

In comparison, he said, 26 million influenza cases have been reported in the United States this season, with 250,000 hospitalizations and 14,000 deaths reported to date.

Calderwood said the response to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak provides some insight into what would happen if COVID-19 began to spread here. “We were having a number of cases in the United States, and we quickly mobilized to get a vaccine available and treatments available,” he said.

Efforts are underway to develop a vaccine for COVID-19, he said, and some treatments are available. “Overall, I would say that this is something that the state is prepared for, that we are actively screening for, that we have testing capabilities for,” he said.

“I would say that my biggest concern actually is the fear that this is generating, because it’s led to some downstream consequences,” Calderwood said.

For instance, a recent run on face masks, which are made predominantly in China, could lead to shortages at health care facilities that rely on them for protection against other infectious illnesses, including the flu, he said.

He also is concerned about “inappropriate targeting of people of Asian descent, thinking that this is a population that is driving this outbreak,” he said. “Whenever we have things like this, I think certain groups get targeted, and I think we have to address this as one nation.”

So far, Daly said, a wide spectrum of illness has been associated with COVID-19, ranging from very mild symptoms to severe illness and death.

New Hampshire is prepared in the event of a “surge” of cases that could overtax existing health care facilities, she said. “In a very bad scenario, you could turn a high school gym into potential care sites for people who aren’t severely ill but need some level of care,” she said.

So why does COVID-19 engender so much fear?

Calderwood blames misinformation shared on social media. His message to the public: “This is something that is actively being monitored, but we have teams ready to care. We have strategies for containment.”

Meanwhile, he said, “We are struggling with something that we see every year and that is killing members of our community. And that’s flu.”

-225x125.jpg)