Harvesting grain and hay crops was done from the end of May until the first killing frost, usually in October. It was backbreaking work begun as soon as the dew dried in the morning until it started to fall again in the evening. Scythes didn’t change much from medieval times until the advent of the grain cradle in the 1700s when “fingers” were added to gather stalks into neat piles. This was the principal method of cutting grain and hay until mechanized harvesters became affordable in the late 19th century. These items from the museum collection date from the mid- to late-1800s. The scythe came from Robert O. Poplin, the grain cradle from Dr. Charles Sykes.

Harvesting grain and hay crops was done from the end of May until the first killing frost, usually in October. It was backbreaking work begun as soon as the dew dried in the morning until it started to fall again in the evening. Scythes didn’t change much from medieval times until the advent of the grain cradle in the 1700s when “fingers” were added to gather stalks into neat piles. This was the principal method of cutting grain and hay until mechanized harvesters became affordable in the late 19th century. These items from the museum collection date from the mid- to late-1800s. The scythe came from Robert O. Poplin, the grain cradle from Dr. Charles Sykes. –

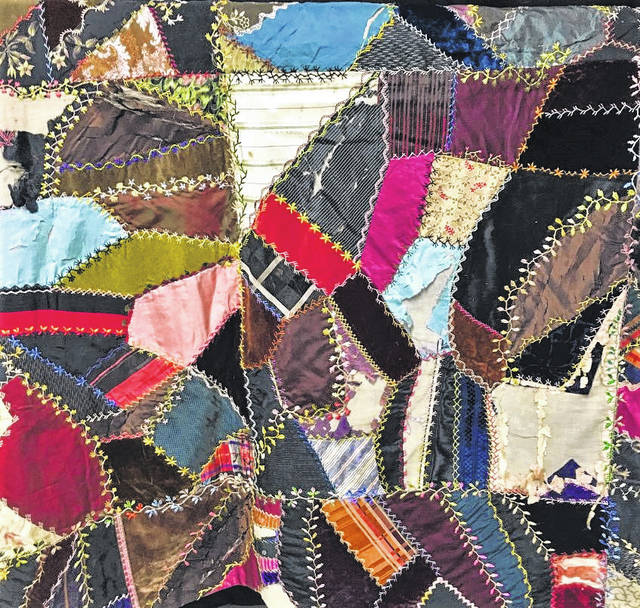

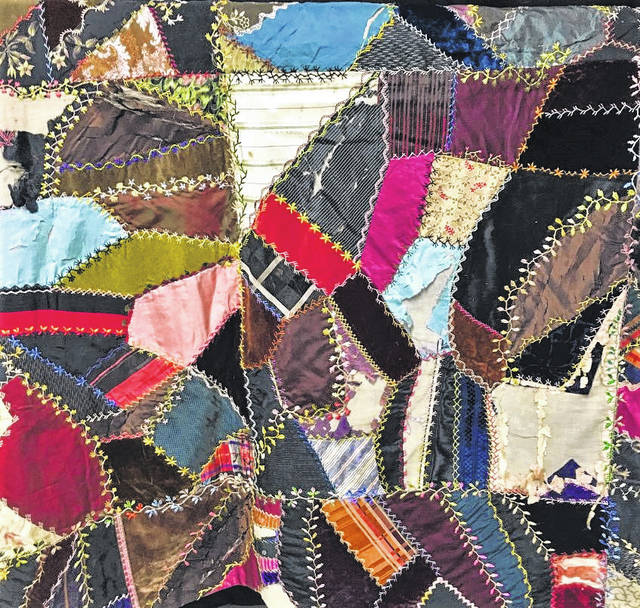

Quilting layers of cloth and batting together creates air pockets that hold heat better than one thick layer. It is found in many cultures around the globe for at least 5,000 years. Patchwork quilting was particularly popular from colonial times in America as a way to use worn out or waste scraps to create blankets. Crazy quilts, like the one shown here, became popular in the late 1800s when someone in Ruth Minnick’s family made this one. More ornamental than practical, the style often used more luxurious fabrics and involved intricate embroidery stitches binding patches. –

Clockwork instruments have existed since the first century BCE. The gears and mechanisms were operated by weights, water, or spring tension created by keys. The technology was applied to timekeeping in the 11th century. F. Lester Dawson, born in the Patrick County, Virginia, learned the watchmaker’s trade after returning from WWII through a government program for disabled veterans. He was the longest working watchmaker in Mount Airy, working 23 years for another shop before opening his own for 34 years on Virginia Street in Mount Airy. –

Mauls are specialized sledge hammers used for a variety of tasks that require brute force to drive posts, stakes, or log splitting wedges. These were all crafted by their owners. The standing tool was made from a persimmon tree root and lower trunk. The others were carved by John “Jack” Simpson in the 1970s while recovering from cancer. They take advantage of natural deformities which are usually tougher. The maul on the left is a knot where the trunk grew a bulge around the base of a branch. The maul on the right is from a tree that was wrapped in a vine. The tree trunk continued to grow, creating the spiral bulge. – –

“Unfortunately for the South there has always been an ingrained prejudice against mechanics,” lamented the editor of the Wilmington Morning Star in February 1885 in a call for state-funded “schools of technology” in North Carolina. “Let some be taught engineering, some become machinists, some carpenters, etc.”

“If a man, in all respects equal to another man who was a merchant or bank officer, became a mechanic he was regarded as socially inferior… Intelligence, moral qualities, industry and skill were and are at a discount in the estimation of the Southern people. The result is unfortunate, and boys are put in shops, stores, etc. instead of keeping them on the farm or putting them at some mechanical calling.”

The words rang true with the editors of the Yadkin Valley News who ran the editorial on the front page here 10 days later.

It could have been written today, almost exactly 135 years later.

Technology — methods, systems, and devices which are the result of scientific knowledge being used for practical purposes — is a word that gets used a lot these days but it’s hardly new. We just think of electronics first now.

Our development and use of technology is one of the things that sets us apart from the animal kingdom. The invention of the wheel, capturing fire, these tools allowed Cro-Magnon man to come out of the caves and build civilizations.

It’s what allowed the flood of European immigrants to forge a nation on the virgin forests of North America.

Part of the Wilmington editor’s point that struck me most deeply is the truth that those who work with their hands are often skilled craftsmen and women. That knowledge, whether it’s how to keep a diesel engine running, how to coax crops from the soil or turn scraps into useful items, is too often disregarded as simplistic requiring no training.

Those who work with their hands, build tools, design new ways to meet old needs more efficiently know better.

The museum’s collection of artifacts show many types of technology used by and, in some cases, crafted by early residents of Surry and surrounding counties. Simple items that our modern minds hardly give a second thought but that represent sometimes significant advances in technology for that age.

Early land records for the region show that technologically minded people who recognized the raw materials here helped establish Surry County as an important business community.

Perhaps the most identifiable natural resource in Surry County is the white granite. The first record of quarrying comes in February 1775 when the Moravian leaders commission two millstones to be crafted by a stone cutter in “the Hollows” as the area that became Mount Airy was commonly called.

The region had deposits of iron ore, absolutely vital for everything from cookware to plows. An 1891 editorial on the front page of the Yadkin Valley News mentions how the plentiful magnetic iron ore made it difficult to trust compasses.

Many mills have been built on the waterways of the area, grist mills, textile, and power generation mills that certainly required both inventive people and those mechanically inclined to maintain them.

Tools were so important in everyday life that, occasionally, they rated a mention in the news.

“Mr. Enoch Creed, of White Plains, will be eighty six years old on the 18th of this month, and he has in his possession a grain cradle which has been in actual use for fifty two years, and in all that time it has never once been repaired, not even to one of its fingers. Cradles made in the days when that one was young must have been more substantial than modern ones.” YVN July 1894

But I find personal items to be just as impressive as the grand businesses. A maul – a sort of specialized sledge hammer – crafted from twisted root wood by the farmer who used it; a quilt that made worn clothing and scrap material useful again — these show the patience, skill and ingenuity of average people doing what was needed to make the most of their time and resources.

Harvesting grain and hay crops was done from the end of May until the first killing frost, usually in October. It was backbreaking work begun as soon as the dew dried in the morning until it started to fall again in the evening. Scythes didn’t change much from medieval times until the advent of the grain cradle in the 1700s when “fingers” were added to gather stalks into neat piles. This was the principal method of cutting grain and hay until mechanized harvesters became affordable in the late 19th century. These items from the museum collection date from the mid- to late-1800s. The scythe came from Robert O. Poplin, the grain cradle from Dr. Charles Sykes.

Quilting layers of cloth and batting together creates air pockets that hold heat better than one thick layer. It is found in many cultures around the globe for at least 5,000 years. Patchwork quilting was particularly popular from colonial times in America as a way to use worn out or waste scraps to create blankets. Crazy quilts, like the one shown here, became popular in the late 1800s when someone in Ruth Minnick’s family made this one. More ornamental than practical, the style often used more luxurious fabrics and involved intricate embroidery stitches binding patches.

Clockwork instruments have existed since the first century BCE. The gears and mechanisms were operated by weights, water, or spring tension created by keys. The technology was applied to timekeeping in the 11th century. F. Lester Dawson, born in the Patrick County, Virginia, learned the watchmaker’s trade after returning from WWII through a government program for disabled veterans. He was the longest working watchmaker in Mount Airy, working 23 years for another shop before opening his own for 34 years on Virginia Street in Mount Airy.

Mauls are specialized sledge hammers used for a variety of tasks that require brute force to drive posts, stakes, or log splitting wedges. These were all crafted by their owners. The standing tool was made from a persimmon tree root and lower trunk. The others were carved by John “Jack” Simpson in the 1970s while recovering from cancer. They take advantage of natural deformities which are usually tougher. The maul on the left is a knot where the trunk grew a bulge around the base of a branch. The maul on the right is from a tree that was wrapped in a vine. The tree trunk continued to grow, creating the spiral bulge.

Kate Rauhauser-Smith is the visitor services manager for the Mount Airy Museum of Regional History with 22 years in journalism before joining the museum staff. She and her family moved to Mount Airy in 2005 from Pennsylvania where she was also involved with museums and history tours. She can be reached at [email protected] or by calling 336-786-4478 x228