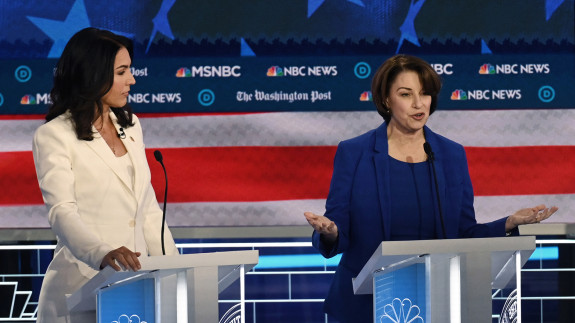

Six months can make a big difference in a presidential race — even if no actual votes have been cast. Back in June, when the primary was still getting off the ground, there were six women in the first Democratic debate, including four senators who all seemed like promising contenders for the nomination. Now, as the Iowa caucuses loom, two of the senators — Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand — are out of the race. And it seems very likely that only Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Amy Klobuchar will make it into this month’s debate.

All in all, it’s not an especially bright picture for the female candidates as the year draws to a close. And the fact that there’s only one woman in the upper tier of candidates hasn’t been lost on Klobuchar, who has repeatedly said that voters hold women to a double standard — drawing a particularly pointed contrast with Pete Buttigieg, the 37-year-old mayor of South Bend, Indiana, who Klobuchar said wouldn’t be taken seriously in a presidential race if he were female.

Of course, it’s not just women who have had trouble breaking out in this race. Not one candidate of color who’s still in the primary is currently polling above 3 percent nationally. And the fact that Warren is still among the top four candidates makes it hard to argue that Klobuchar’s single-digit support is due mostly to sexism. That doesn’t mean, though, that gender isn’t playing a role.

Several experts told me that the research does suggest that Klobuchar’s claim — voters hold women to a higher standard than men — holds up. A number of studies have found that voters don’t easily move past women’s stumbles, and are less likely to view women as qualified or competent to begin with. And women’s qualifications can even be turned into liabilities.

The precise effect of these attitudes is hard to pin down, but gender biases and stereotypes are a kind of headwind blowing against female candidates — a force that can be overcome but constantly threatens to slow women’s momentum. “Even in a Democratic primary, when they’re faced with two equally qualified men and women, many voters will default to the man,” said Nichole Bauer, a political science professor at Louisiana State University who studies gender and politics. “It’s a challenge for women to break even with their male rivals, much less win.”

Voters are likelier to punish women’s mistakes

Harris’s campaign had a lot of problems, as my colleague Perry Bacon Jr. has explored at length. Some of those were outside her control — she had strong competition, for instance. But she also struggled at several key moments to explain why she was running for president and made several missteps along the way. Her peak in the polls came after the first debate, when she took on former Vice President Joe Biden for his stance on school integration. But her support quickly receded to its pre-debate levels — perhaps because the attack backfired, or because she couldn’t offer a proposal of her own on the issue. Additionally, months of confusing messaging on health care culminated in a much-criticized rollout of her health care plan, which was assailed by rivals on both her left and right. By the end of the summer, Harris was polling in the single digits, and she never really recovered.

It’s hard to know how those mistakes would have played out if she were male. But there is evidence that voters are much less forgiving of female candidates when they stumble, which may have meant that Harris’s missteps had more sticking power. Amanda Hunter, the research and communications director of the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, a nonprofit group that researches gender bias and elections, said that voters assume that women candidates are more ethical and honest than men, which can be a bonus until women candidates do something that makes them seem like they have something to hide. “Because voters expect women to be more virtuous and straightforward, they’re more likely to hold it against female candidates when their honesty is questioned,” Hunter said. That “pedestal effect,” she added, may have hurt Harris when she was attacked for going back and forth on issues like health care.

Research indicates there’s also a narrower band of acceptable behavior for female candidates, who have to navigate conflicting expectations for women and for leaders. This adds another layer of difficulty, because on top of the fact that there’s less room for mistakes, voters are also more likely to punish female candidates for failing to strike the right balance between the stereotypically feminine behavior that’s expected of women and the stereotypically masculine behavior that’s expected of political leaders.

For instance, voters often want a leader who is perceived as aggressive, but aggression in women can also be perceived as threatening. Harris was known for her direct, prosecutorial style and Bauer said that her identity as a woman of color may have put her in an even tighter bind. “Black women are often stereotyped as angry or militant,” Bauer said. It’s hard to isolate exactly why Harris’s plunge in the polls was so dramatic and decisive, she added, but “if there was a negative reaction to her attack on Biden at the debate, those stereotypes may have played a role.”

Women’s qualifications can become liabilities

Whether or not gender is holding back Klobuchar or the other female candidates, several experts told me she’s correct that a woman with Buttigieg’s background would be much less likely to be taken seriously in a presidential race. Bauer’s newest study showed that voters generally hold female candidates to a higher standard than men, which reinforces other work indicating that although women do tend to win at the same rate as men, they’re often more qualified than their male counterparts.

That’s because our internal sense of what a political leader looks and sounds like can overshadow the content of a candidate’s resume, or even change how his or her political accomplishments are perceived. For instance, a study by Tessa Ditonto, a political scientist at the University of Durham, showed that when participants received a piece of information indicating a woman was less competent, her support fell dramatically — but there was no similar impact for men. “It speaks to the idea that voters tend to be more uncertain about women candidates,” Ditonto said.

So a long list of accomplishments and experience is pretty much mandatory for a female candidate, especially one running for executive office. But an impressive track record can also lead to even more negative scrutiny.

Think back to when Buttigieg announced his candidacy last spring. He flew under the radar for a bit, but then received an avalanche of positive media coverage, echoing the glowing profiles written about former Rep. Beto O’Rourke, another relative newcomer. Harris and Klobuchar, meanwhile, were greeted almost immediately with critical articles highlighting their backgrounds as prosecutors or — in Klobuchar’s case — mistreatment of staff. “For women to get the right kind of experience to be taken seriously, they have to behave like men,” Bauer said. “But then that behavior is often scrutinized and criticized more harshly than it would be in a man, because it runs counter to what our stereotypes of a woman should be.”

In theory, these aren’t insurmountable barriers, but Ditonto said that it’s likely that even Warren is being held back by a slew of gender bias and stereotypes, particularly in a race where primary voters are laser-focused on nominating a candidate who can beat President Trump. According to two polls by the left-leaning group Avalanche Strategy, for instance, Warren is more popular when voters are asked to pick which candidate would be their favorite if they could magically bypass the general election, which suggests that some voters still have concerns about her viability despite her rise.

And those doubts, too, could be shaded by gender. “Competence and qualifications are often closely linked to viability in voters’ minds,” Ditonto said. “So even though Warren has been doing better than the other women in the race so far, that uncertainty voters seem to feel about female candidates could still be hurting her.”