Image copyright

ESA

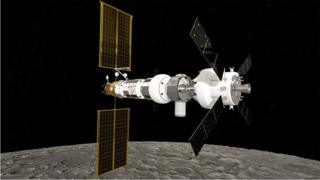

Artwork: How the Esa-propelled Orion ship would look at the Gateway

The Europe Space Agency (Esa) will show its commitment to the new wave of lunar exploration when member-state research ministers meet in Seville, Spain, next week.

The politicians are expected to commit hundreds of millions of euros to fund technologies that will support the US-led Artemis project to return humans to the Moon.

Included will be the money to complete two propulsion-cum-service modules that are needed to push the Americans’ Orion crew capsules through space.

These spacecraft, which will take part in the Nasa missions known as Artemis 3 and 4, are scheduled to fly from 2024 onwards.

They will witness the first astronaut sorties to the lunar surface in nearly 50 years.

Also set to be nodded through by ministers at the Seville Council is development work on the international lunar space station, known as Gateway.

Europe wants to contribute a habitation module (iHab) and a second multi-purpose unit that would enable access, refuelling, and high-data-rate communications to the Moon’s surface.

Dubbed Esprit, this unit would come with big windows through which the Gateway’s live-aboard astronauts could monitor robotic operations on the exterior of the station but also look down on the Moon and back to Earth.

Image copyright

ESA

Dr Parker: “The objective” is to see European astronauts on the Moon’s surface

The menu before research ministers at their Seville Council (PDF) doesn’t end there. Esa officials also envisage a large autonomous freighter that could deliver supplies to astronauts working on the lunar surface.

It wouldn’t fly until later in the next decade, but engineers need to begin the design work now.

“We want to do a robotic Moon mission that is part of the human exploration,” explained Dr David Parker, who directs the agency’s human and robotic exploration programmes.

“Basically, we’d like to be able to send a cargo vehicle to the Moon – to take the food, the rovers; whatever you need for long-term sustained exploration on the surface. And that vehicle could also do science by bringing rock and soil samples back up to the Gateway,” he told BBC News.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Dr Parker will be laying a near-€2bn request before ministers next week – a step up from the €1.5bn approved at the last major Council in Lucerne in 2016. And while ambitions at the Moon currently catch the eye, Europe has also to maintain its infrastructure just above the Earth.

Its Columbus science lab, which has been a part of the International Space Station (ISS) for almost 11 years, is going through a modernisation programme. Esa will be updating the lab’s ground support and attempting to bring in new players to use the facility.

Dr Parker, a former chief executive at the UK Space Agency, has within his remit robotic exploration at Mars.

This includes the Rosalind Franklin rover, which is set to launch to the Red Planet next July, assuming the troublesome parachutes on its descent-and-landing system can be made ready in time. The chutes are in the midst of a make-or-break test programme.

Image copyright

Max Alexander/Airbus

The Rosalind Franklin rover is scheduled to launch to Mars in July next year

The Council must approve the next tranche of money for the project, which will be used in part to fund the six-wheeled vehicle’s operation on the Martian surface. But ministers will also be asked to turn their minds to “what comes next”.

This is Mars Sample Return – the quest to bring back rock and dust samples to Earth labs for study. These samples will be chosen and cached in small canisters by the US space agency’s (Nasa) big 2020 rover.

The one-tonne robot will drop the canisters on the ground and it will be the job of a later European “fetch rover” to go around and retrieve them.

Dr Parker wants money to push forward development activities – for this small rover and a European spacecraft that would do the transfer of the samples from Mars to Earth.

“There is a robotic arm involved that we need to work on too. This would take the sample tubes from the fetch rover and load them into the Mars ascent vehicle from Nasa. The ascent vehicle – essentially a rocket – takes the sample tubes up to the European orbiter.”

UK industry and academia have interest in many of these projects. For example, they’re keen to get involved in the communications aspects of the Esprit module; British engineers would like also to work on the propulsion system that takes the Moon freighter down to the surface; and having been responsible for the assembly of Rosalind Franklin, there is eagerness to lead the fetch rover.

In addition, Britain is looking for support from other member states in Seville to help take the Lunar Pathfinder concept to the next level. This is a commercial service that Esa would purchase.

It envisions a mothership-type spacecraft, to be built at SSTL in Guildford, that would ferry smaller satellites to the Moon’s vicinity and then relay their communications back to Earth. Other Esa nations or commercial concerns could book a ride on pathfinder.

The head of the US space agency, Administrator Jim Bridenstine, recently wrote to his Esa counter-part, Director General Jan Wörner, inviting Europe to play a major role in the Artemis missions.

The Nasa chief said he hoped to see a European astronaut on the lunar surface in the near future. This is ultimately the goal, confirmed Dr Parker.

“What we’re doing at this ministerial is laying the ground in steps that would get Europeans to the surface of the Moon. That’s the big objective,” he told BBC News.

“It’s not tomorrow, because it’s not going to be tomorrow for anyone. But that’s absolutely what we’re working towards.”

It will probably mean new astronauts will need to be recruited and trained – a process that takes five years. “This is a specific decision member states would have to make; when they want us to do that. But it would make sense to start thinking about the post-2025 era,” Dr Parker said.

Image copyright

NASA/ESA