The Political Declaration on Universal Health Coverage, adopted recently at the United Nations General Assembly, could set the stage for a fairer world in which health is viewed as a human right and not as a commodity. On paper, we have a compact that enshrines the idea of universality. At the local, state, and country levels it will mean healthier populations and greater global health equity.

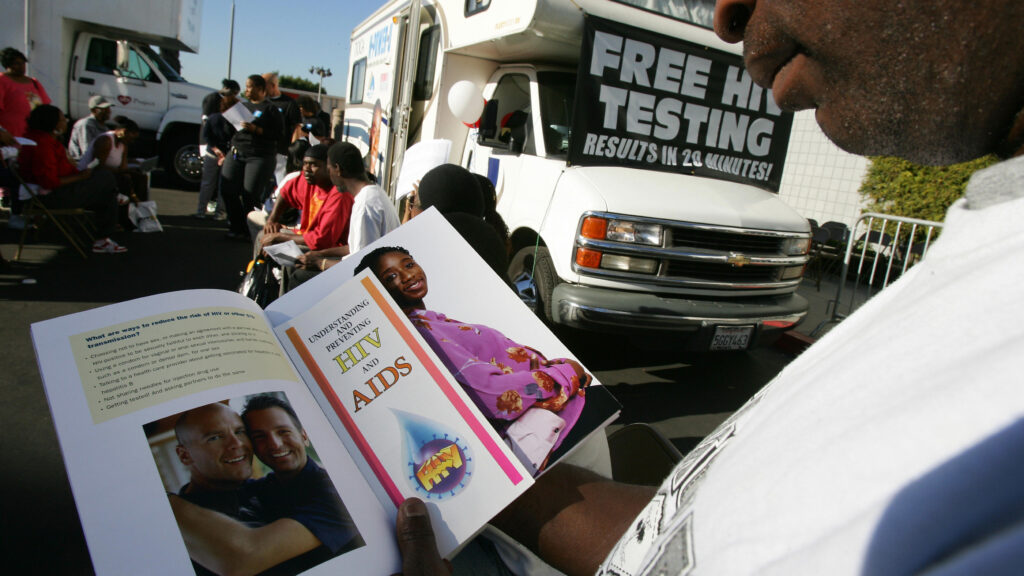

Moving from declarations to reality won’t be easy. Lessons from the response to the AIDS epidemic over the past four decades and the evolving response to the global emergency around noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) clearly demonstrate that community engagement and human rights must be front and center.

Consider this: Gay men led the fight against AIDS. They were the human face of the epidemic and in the early days suffered enormous discrimination at all levels of society. We now know from their experience that if we are to defeat this epidemic — and others — we must remove stigma around the disease. Gay men also led the move to drive home the importance of HIV prevention and safe sex; pushed for governments and the private sector to invest in anti-HIV drug research; and offered to take part in trials of these drugs.

advertisement

Today, some 23 million people around the world are on HIV treatment. While the job is not yet finished, it is no exaggeration to say that this is one of the great public health achievements of the last 50 years.

For decades, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) has fought for civil society and communities to gain a seat at the decision-making table, from the global level to the local. Above all, UNAIDS made it unthinkable to discuss the response to HIV without involving people living with it. Today, communities affected by HIV are present at all levels of the response. Their partnerships with government, the private sector, and the research community is, in many countries, the gold standard for fighting this disease.

Communities most affected by HIV/AIDS are also in many cases the same communities providing prevention and treatment services to people affected by or living with the virus. Past and present sex workers provide legal services for sex workers in Cape Town, South Africa. The East African Drug Users Network provides harm-reduction services and advice to people who use drugs. Tinerii pentru Dreptul la Viata (Youth for the Right to Live), a community-based organization in Balti, Moldova, partners with the municipality to provide tuberculosis and HIV care in ways that reduce stigma and discrimination. Between 2016 and 2018, this program saw a 42% decrease in TB-related deaths.

On the other side of the world, the AIDS Council of New South Wales in Australia provides a range of HIV prevention, treatment, and counseling services to Sydney’s large gay male population. Many of the council’s staff members are themselves from this community.

As the gravity of the noncommunicable disease epidemic dawns on policy makers, it is encouraging that community-based solutions are also becoming integral parts of the response to it. The challenge is significant. The World Health Organization estimates that noncommunicable diseases kill 41 million people each year, accounting for 71% of all deaths globally. Some 15 million of these deaths occur “prematurely” in people between the ages of 30 and 69 years.

No amount of scientific or medical knowledge can replace the insight of the lived experiences of people affected by an illness. In 2017, the Noncommunicable Disease Alliance, whose network includes more than 1,000 member associations working in this sector, consulted with nearly 1,000 people living with NCDs in Ghana through in-person community conversations and an online survey to build the Ghana Advocacy Agenda of People Living with NCDs and helps shape national NCD prevention and control efforts. This model has since been adapted by national NCD alliances in Kenya and Mexico.

In Kenya, a breast cancer survivor started weekly events in Cancer Café that offer a space for people affected by cancer and their families to share their experiences and explore avenues to link people living with and affected by the disease with relevant health care providers.

The wisdom of the mantra “nothing about us without us” is not lost on people affected by noncommunicable diseases. What they want most is a holistic, integrated approach to health care, from prevention through palliative services, that listens to, understands, and responds to complex and individual needs by putting people at the heart of the design and delivery of health services.

Measures like those being taken by UNAIDS and the NCD Alliance to engage and consult closely with people living with and affected by HIV and noncommunicable diseases will potentially provide a blueprint for the wider health sector going forward.

A growing body of evidence demonstrates the impact and cost-effectiveness of community-led service initiatives and delivery. In the case of HIV, UNAIDS’ global strategy recommends that countries expand their community-based HIV delivery to cover at least 30% of the total HIV/AIDS services provided globally.

Questions remain about how this can be achieved when we are seeing a growing trend of shrinking space for civil society. From 2012 to 2015, more than 120 laws restricting the rights of civil society organizations were introduced or proposed in 60 countries, thus limiting their capacity to fulfill their essential missions: calling for the right to health for all to be upheld and delivering results for the people they serve.

If universal health care is truly meant to reflect meaningful community engagement, governments need to invest in the leadership and capacities of the diverse communities of people directly affected by NCDs and infectious diseases.

Scaling up health prevention and treatment from millions of people to billions of people cannot be achieved by governments alone. It will require more training and resources for community-led services that enable communities and governments to better work together. Support for communities has never been so urgent to help them challenge exclusion from decision-making, poor public services, corruption, and the inequality they see daily.

We also need more transparent ways to measure how well we’re doing. Because countries need to be accountable for the promises they make, we need effective and transparent instruments that can measure progress — or the lack of it — to ensure that universal health coverage places people and their rights at the center and leaves no one behind. With rigorous independent processes to assess the quality of services, universal health coverage will improve health around the world. And quality health for all is surely the endgame.

Gunilla Carlsson is the acting executive director of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Katie Dain is the CEO of the NCD Alliance. Rico Gustav is the executive director of GNP+, the Global Network of People Living with HIV.