Scrawled flow charts and a mission statement for blockchain adorn the meeting room, while an early bitcoin mining processor stands on a table next to a dispenser of M&Ms, Skittles and spicy pumpkin seeds. Swivelling, speech-sensitive video conferencing cameras add to the sense of earnest tech feng shui.

It could be a scene from any sketchy Silicon Valley cryptocurrency endeavour. Yet this is a room at the plush Boston headquarters of Fidelity Investments, a storied but historically staid corner of the finance industry.

The venerable money manager has since its founding by Edward Johnson in 1946 become a byword for the mutual funds that rose to prominence and dominated markets over the past half-century. Several generations of superstar stockpickers like Gerald Tsai, Peter Lynch and today William Danoff have helped expand its assets under management to $2.8tn.

But that is merely one part — albeit a big, lucrative one — of a vast empire that services millions of investors, traders, banks and retirees across the world. All told, Fidelity administers another $7.7tn on behalf of various clients, making it one of the biggest, broadest and most powerful financial groups in the world.

The investment industry has come under intense pressure in recent years, buffeted by falling fees and rising costs. Abigail Johnson — the founder’s granddaughter who picked up the reins five years ago — is trying to reforge Fidelity for a new era, where technology permeates and reshapes every aspect of the company’s disparate businesses.

“Across all financial services, the trend is towards fee compression . . . Every aspect of the business, customers expect you to do more in terms of service and offerings, and they expect to pay less for it,” Ms Johnson says. “It means that we’ve got to be ahead of that. We’ve got to do more with the same number of people every year.”

Its dabbling in cryptocurrencies — Fidelity mined its first bitcoin in 2014, which now sits on the corporate balance sheet — has attracted the most attention, given the clash between its wild-west nature and the Boston institution’s conservative image. But Ms Johnson is now spending about $3bn a year on tech to modernise every business line, from trading to retirement planning.

“Financial services is becoming another winner-takes-all industry, so you need to spend a lot of money on tech to get the advantages of scale and play both offence and defence,” says Huw van Steenis, a veteran industry analyst who now works at UBS.

But the question is whether an organisation as big, established and complex — and with a culture as ingrained as Fidelity’s — can evolve quickly enough to navigate the industry’s ferocious headwinds.

“Every business house has to change,” Ms Johnson admits. “If you don’t change, you’re by definition either on your way to atrophy or you are atrophying. The world changes. You have to evolve your business and challenge yourself to say, ‘Where are things going?’”

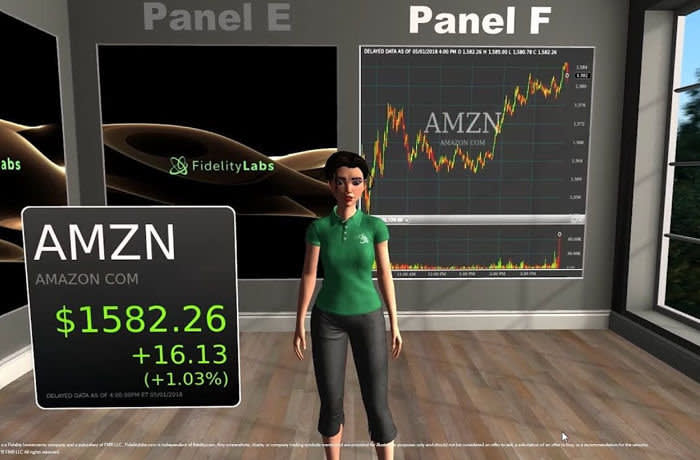

The finance industry can often appear surreal to outsiders, but Fidelity is exploring whether virtual reality can make it more palatable to consumers.

Adam Schouela at the Fidelity Center for Applied Technology enthusiastically shows off a virtual space that customers can use as a fun way to plan their financial future. The gaming-like environment may still be at an early stage, and currently mainly used to train Fidelity staff. But Mr Schouela sees it as emblematic of the company’s willingness to test out-there technologies and see if they might be relevant to Fidelity.

“One of the requirements for a project is that we must legitimately not know what the answer is going to be. If I know for sure it is going to work, then it’s probably not for us,” he says. “In going all the way to the extreme, we can actually see things that we might otherwise not necessarily have seen.”

Sometimes an initiative may initially appear like a waste of resources, such as building a Fidelity application for the Pebble smartwatch that launched to great fanfare in 2013. It proved a damp squib, and was quickly discontinued. But Fidelity’s work proved valuable when Apple unveiled its own smartwatch in 2015, helping the asset manager have an app ready on its launch.

The technology centre is also where Fidelity’s initial bitcoin experiments took place, which last year evolved into a standalone company, Fidelity Digital Asset Services. What was initially just a “fun” experiment is now being rolled out as a major service to the cryptocurrency industry, Ms Johnson says.

Managing money remains Fidelity’s biggest business, but there too changes are afoot. Although her father Edward “Ned” Johnson was himself a bit of a tech geek — Fidelity was one of the first big asset managers to install a mainframe computer in 1965 — the company is today seen as somewhat old-fashioned, and dependent on mutual funds.

However, Ms Johnson has embraced the index funds once mocked by her father. Fidelity now has about $530bn in passive funds, making it one of the biggest providers. Last year Fidelity sent asset manager’s shares tumbling when it introduced the first free index fund, escalating the price war.

In another sign of the times, Fidelity last year promoted Steve Neff, its chief technology officer, to lead its $2.8tn asset management division. Although he had worked in that unit before, Mr Neff had never done a front-line investing job himself.

“What I bring to the table is how the technology and the digital transformation the company is going through applies to the asset management business,” he says. “Many problems are now addressable through technology, so we can expand our horizons.”

Although asset management is the biggest money-spinner, the Fidelity empire is sprawling, and in many cases growing more rapidly than the heartland. At the end of June, Fidelity boasted 33m workplace and healthcare plan participants and 22m retail client accounts. There are another 10m accounts, with other investment intermediaries, on its clearing and custody platform.

“The pace of technological change is accelerating, and I think it will go even faster. The question is how we can accelerate as well,” says Kevin Barry, head of workplace investing, which provides retirement, investments and benefits solutions to more than 20,000 companies and millions of employees. “The technology that got us here isn’t the technology that will get us to the future.”

Fidelity Institutional, which sells brokerage, custody, tax and reporting services to financial advisers, insurers, family offices and even some hedge funds, last year launched Wealthscape Integration Xchange. This is a kind of digital store that wealth managers can use to build their own platforms using both Fidelity services and more than 100 third-party ones. According to Michael Durbin, head of Fidelity Institutional, the “fintech explosion” is changing almost every aspect of its offering.

Many “quantitative” investment groups are sceptical that traditional companies like Fidelity will be able to spray money at modish tech projects and retool their business in a meaningful way, comparing it to turning an oil tanker in a tight canal. By that logic, Fidelity is an ageing supermax vessel.

“It’s genuinely difficult,” especially on the asset management side of Fidelity, according to an industry analyst, who declined to be named. “A lot of asset managers are spending a lot of money on computer scientists, and they don’t end up being used.”

Upgrading Fidelity’s core tech infrastructure — which was largely developed in the 1980s — is time-consuming and expensive. “We did the same thing everybody in the industry did, which was you started creating apps and we put the apps on top of the old technology,” says Ms Johnson. “And it works, but then at some point you realise OK, this is not the best way to do things.”

Moreover, Fidelity employees are steeped in a certain way of doing things that goes back generations. That will be hard to change, though Fidelity is also attempting to retool its culture.

The finance industry as a whole is attempting to improve its image and become a broader, gentler church, and Fidelity in particular has a reputation for being dominated by male, Irish-American, middle-class, beer-drinking Red Sox fans. Even Amy Philbrook, the company’s head of diversity and inclusion, ruefully admits that she fits four of those clichés.

“Humans are wired for bias,” she says. “It’s an industry issue, not just for Fidelity. We need a reputation makeover as an industry.”

But she hopes that technology can help here too. For example, Fidelity is using artificial intelligence to write more neutral job ads shorn of subconscious biases, to test the outcomes, and to better target job sites that might have more prospective hires from minorities.

“It’s a little fraught, but I’m excited about how technology can help disrupt human bias in the decision-making process,” she says. “But that requires that you are diligently auditing the technology itself to make sure that bias isn’t hard-wired into it. You have to constantly screen and rescreen your algorithms for biases.”

This became more pressing after Fidelity let one of its star stockpickers go in 2017 amid accusations of inappropriate behaviour. That led to a wider shake-up of the equities division, and Ms Johnson relocated her office to the unit’s 11th floor home so she could keep a closer eye on the group herself.

“I’d like to remind everyone that we have no tolerance at our company for any type of harassment. We simply will not, and do not, tolerate this type of behaviour, from anyone,” she said in a company-wide message at the time.

The shake-up is even taking place in the physical and organisational realm. Fidelity Personal Investing in 2017 embraced the fad for “agile working”, carving out “squads” of 5-10 people, scrapping cubicles and embracing hot-desking. This is now being rolled out across more areas.

“Changing the physical layout was a big thing,” says Ram Subramaniam, head of brokerage and investment solutions at Fidelity Personal Investing. “It isn’t enough to use new technology. To become a truly digital company, we need to change how we work.”

Financial comfort gives Fidelity a good springboard to make some big leaps. Last year it reported record operating income of $6.3bn. That’s even greater than BlackRock’s $5.5bn.

“They have a lot of ingredients for success,” says the industry analyst. “[Fidelity] has scale, and they’re so profitable that they can afford to invest a lot on upgrading their technology.”

Yet Ms Johnson admits that profits may be hit. “You’ve got to have your nose to the grindstone to keep your cost curve ahead of the expected fee compressions. That is not a recipe for expanding margins,” she says.

Nonetheless, Fidelity’s chief executive is confident that the breadth of the family company — which none of its main rivals can match — will ensure that she can hand it over to the next generation of Johnsons in even better shape.

“Even though we might see fee compression in . . . areas of the business, that scale, that depth and breadth of the clients that we serve, the marketplaces that we’re in, the adjacencies that we can build, even if they’re small today, they might grow huge,” she says.