Getty

Once upon a time, many thought the internet would spawn a digital democratic utopia: harmonious, boundary-spanning decision-making, reflecting liberty and equality in a global community of “netizens.” Today, sadly, we witness identity theft, cyber-bullying, manipulative analytics, fake news, and authoritarian surveillance— hacking elections and polarizing open societies. Social media companies are hiring thousands of editors to fight hate speech and robotic information corruption, while U.S. state election commissions are scrambling to reinstate paper ballots. Will today’s democracy survive the onslaught of technology-delivered malice?

Polity Press, 2019

By permission of the author

Yes, maybe: but only if we stop blaming bits and bytes, forget about “global democracy,” and instead tackle the structural deficits of our current representative systems of national self-governance. Thus argues Dr. Roslyn Fuller, a Canadian-Irish academic lawyer and author of the new In Defence of Democracy.

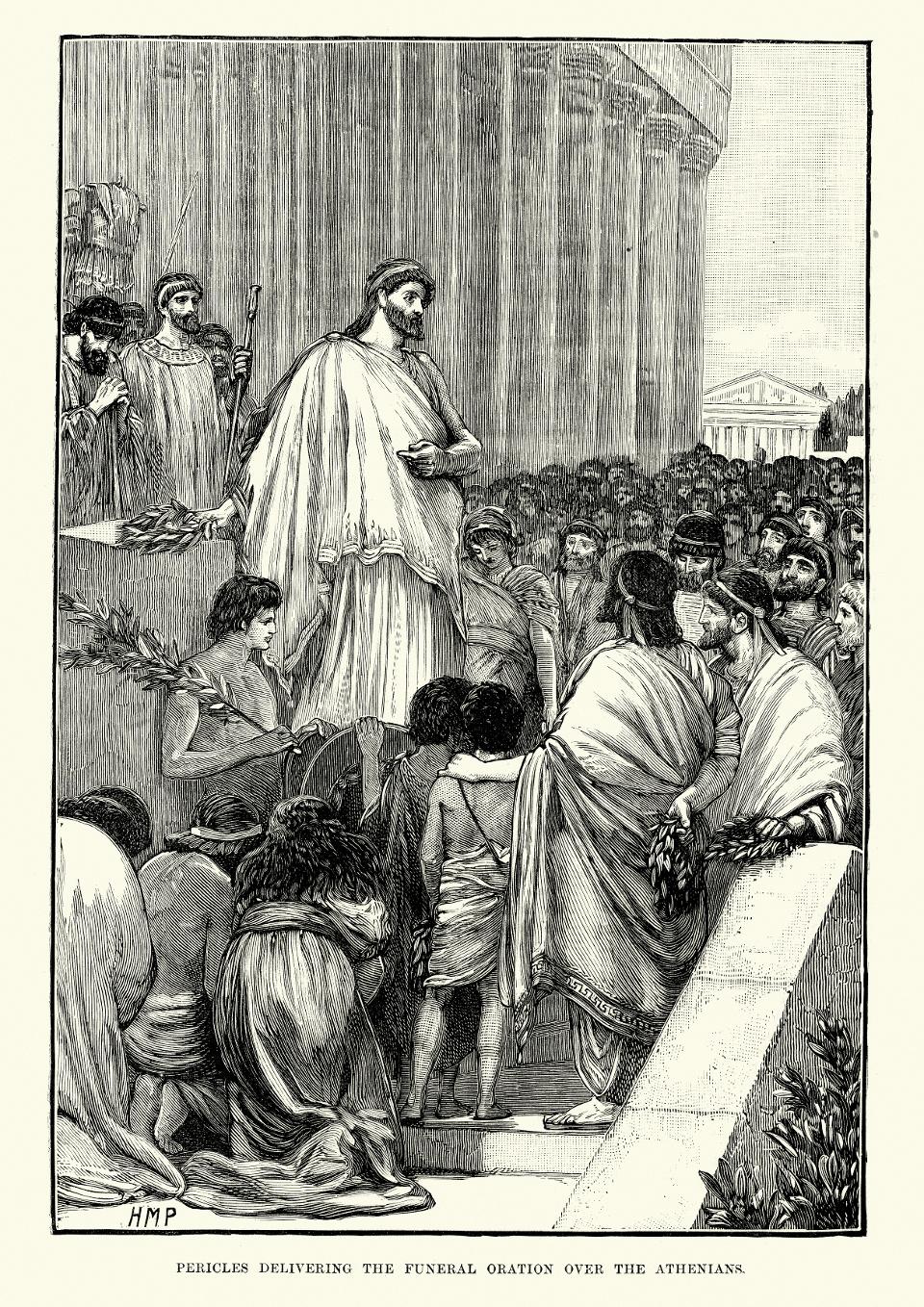

This lively polemic asserts that the problem for western civic societies is not so much defending against hostile and abusive use of technology. Instead, it’s failing to use technology to rediscover what democracy should be for the modern nation state: citizens participating personally in public debate and having meaningful say in policy decisions that affect them—without the distorting and corruptible role of legislative proxies or elitist agency officials. If we’re going to defend—and keep alive—democracy today, she insists, we need a revolution: go back to what the ancient Athenians invented in the 5th century BCE, where every citizen regularly participated in discussion and voting for the laws that would steer their livelihoods and survival. Dr. Fuller believes new technology and communication tools can now provide the means to scale up for millions of people what ancient Athenians did with perhaps (at most) 50,000 citizens.

Roslyn Fuller

Brad Ateke

The book builds on Fuller’s earlier research, further detailing her back-to-the-future proposition. Her central premise is that any modern representative democracy— e.g. U.S. constitutional government, or Britain’s “monarch-lite” parliamentary model—will inevitably slide towards a gridlocked, gerrymandered, influence-peddled partisan morass. “The small number of seats in legislatures serving a major population means elections aren’t really representative—allowing money to grow in influence, which in turn sets up factional fighting and winner-take-all strategies. Meanwhile, what these representatives discuss is increasingly out of touch with most common people’s priorities—leading to rising frustration, disengagement, and declining voter turnout. Which then invites more winner-take-all by powerful interests and increasing partisan focus on policy that entrenches elites. To break the cycle we have to authentically give power back to the people.”

Why not reach for some blue sky ideas?

Getty

Re-imagining Reinvention

Yes it’s blue sky, and of course fraught with a host of implementation issues (e.g. levels of geographical engagement, infrastructure design, process protocols, security assurances, discussion moderation, etc.). But take a moment to consider other alternatives: what will it actually take “to fix today’s democracy?” Is limiting campaign contributions, changing the tax code, or reforming the Electoral College going to be enough to rebuild freedom, equality, and the pursuit of happiness across America?

Here are five further insights from our conversation for your own imaginative reflections:

1. Technology for large-scale, direct democracy is less about elections and more about empowering policy debate and decision-making en masse. Fuller acknowledges the problems of hacked balloting and cyber-meddling—but no election reform will solve the bigger problem of disconnected citizens working through proxies: “A few hundred legislative members or a president can be easily corrupted by rich powerful lobbies. Which now happens every day. Also, the current pace of decision-making, and the two- or four-year cycle of change in representative government can’t keep up with the global economy. Using technology to give millions of citizens direct involvement in policy-making is faster and more flexible. And lobbyists can’t bribe or intimidate the population of an entire nation state.”

2. Our corrosive political media thrives because virtual conversations are untethered from policy consequences. “Yes of course,” Fuller acknowledged, “we need safeguards against cyber-bullying and moneyed and foreign influence shaping opinion. But Facebook diatribes, Twitter wars, and cable shout-fests keep growing because people can’t turn their own strongly held opinions into action. Give citizens a real say in policy-making, and the cyber negativity will decline.”

3. Reforming democracy with technology-scaled participation requires practical citizen education. Everyone agrees that improving our political system calls for better “civic knowledge” across the population. But that can’t just be more high-school courses on “how a bill becomes a law.” Dr. Fuller argues from another lesson of ancient Athenians: “Education has to be learn-by-doing for all the citizens, all the time: participating in public debate, developing your own opinions by hearing and joining arguments, and observing the consequences of decisions—which are often painful.”

Pericles (c. 495 to 429 BC), the most prominent and influential Greek statesman, orator and general of Athens during the Golden Age

Getty

“A lot of American and European cities are successfully experimenting with this form of practical civic education with ‘participatory (or open) budgeting’—allowing citizens to debate and decide how to allocate the public money of their community. The process creates vivid civic lessons about the prioritizing and compromising necessary in a democratic society.”

4. Mass engagement could rebuild fractured communities. Fuller also argues for second-order effects of mass engagement. If millions of citizens participate in political decisions—with appropriate facilitation, rules and encouragement (including some offsetting compensation)— the process can help temper partisan divisions, and build new civic relationships. “When the outcomes of debates concretely effect people’s future, citizens learn to listen to one another, and work for solutions that everyone has to live with. They see that, instead of always pushing for ‘the scientifically perfect answer,’ sometimes accepting compromise can bring other people in, and unify support. Joining together for action strengthens community bonds.”

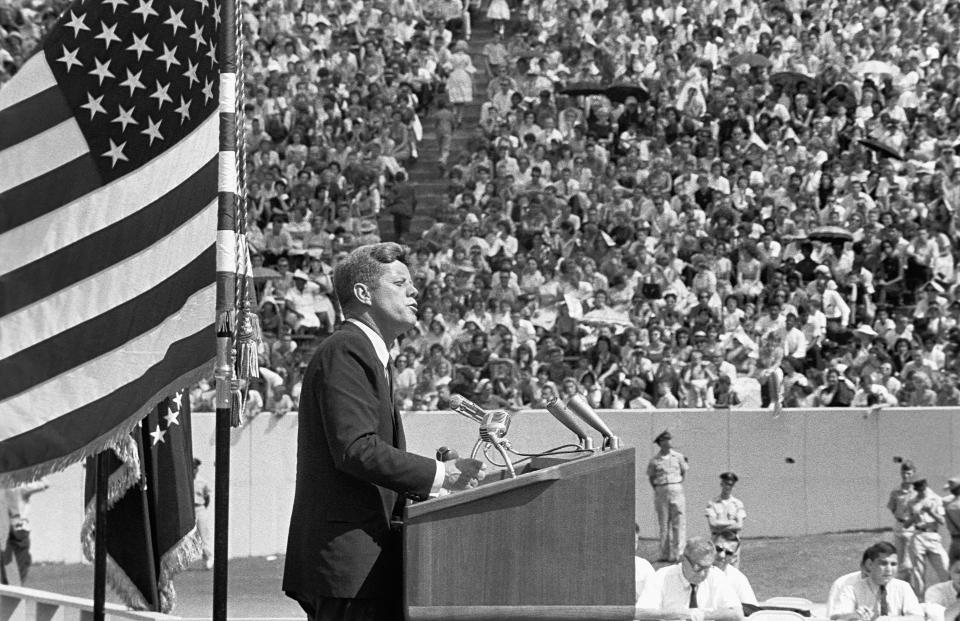

5. Transformation will depend on leaders with a vision for challenge and excellence. “We need a new generation of politicians who can create a positive vision of what democracy can do. A citizenry responds to challenge—like that posed by John Kennedy’s legendary speech in 1962 to America: ‘We choose to go the moon in this decade, and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.’”

President John F. Kennedy gives his ‘Race for Space’ speech at Houston’s Rice University. Texas, September 12, 1962.

Corbis via Getty Images

“And we also have to get away from today’s victim mentality. The ancient Greeks and Romans accomplished a lot with very little—their politicians made the higher call for excellence. Likewise, tomorrow’s leaders cannot just think about themselves. They have to inspire us with what a better democratic future means for all the citizens—and get us all involved to share the task: building a more prosperous society, with a renewed middle class, and where every individual can flourish and reach his or her full potential.”

Iowa Caucuses in the 2016 Presidential Election

Getty