Image copyright

NASA

Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins practises in the simulator in June 1969 – one month before launch

Fifty years on, the Apollo Moon programme is probably still humankind’s single greatest technological achievement.

On 16 July 1969, astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were strapped into their Apollo spacecraft on top of the vast Saturn V rocket and were propelled into orbit in just over 11 minutes. Four days later, Armstrong and Aldrin became the first humans to set foot on the lunar surface.

Here’s a visual guide to four lesser-known facts about the history-making mission.

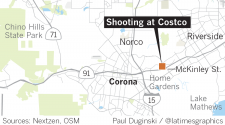

1. Saturn V is still the largest and most powerful rocket ever built

Standing at more than 100m (363ft), the Saturn V rocket burned some 20 tonnes of fuel a second at launch. Propellant accounted for 85% of its overall weight.

“I think we were all surprised at how strong that thing was,” Apollo 8 astronaut Frank Borman said in 2011.

Astronaut Charlie Duke likened the feeling of stage separation – when parts of the spacecraft are jettisoned – to a “train crash”.

Image copyright

NASA

Saturn V: Engineering on a vast scale

Saturn V weighed 2,800 tonnes and generated 34.5m Newtons (7.7m pounds) of thrust at launch.

That’s enough to lift 130 tonnes into Earth orbit, and send 43 tonnes to the Moon – the equivalent weight of almost four London buses.

2. Apollo’s crew compartment was about the same size as a large car

Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins spent eight days together travelling almost a million miles to the Moon and back in a space roughly the size of a large car.

The astronauts were strapped into bench-like “couches” during launch and landing in the Command Module, which measured 3.9m (12.8ft) at its widest point.

It was no place for the claustrophobic.

Image copyright

Getty Images

The Command and Service Module of Apollo 17 pictured from the Lunar Module

Behind the Command Module came the Service Module, which contained fuel tanks and engines.

The Lunar Module (LM or “Lem”) was carried in a compartment behind the command and service modules.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

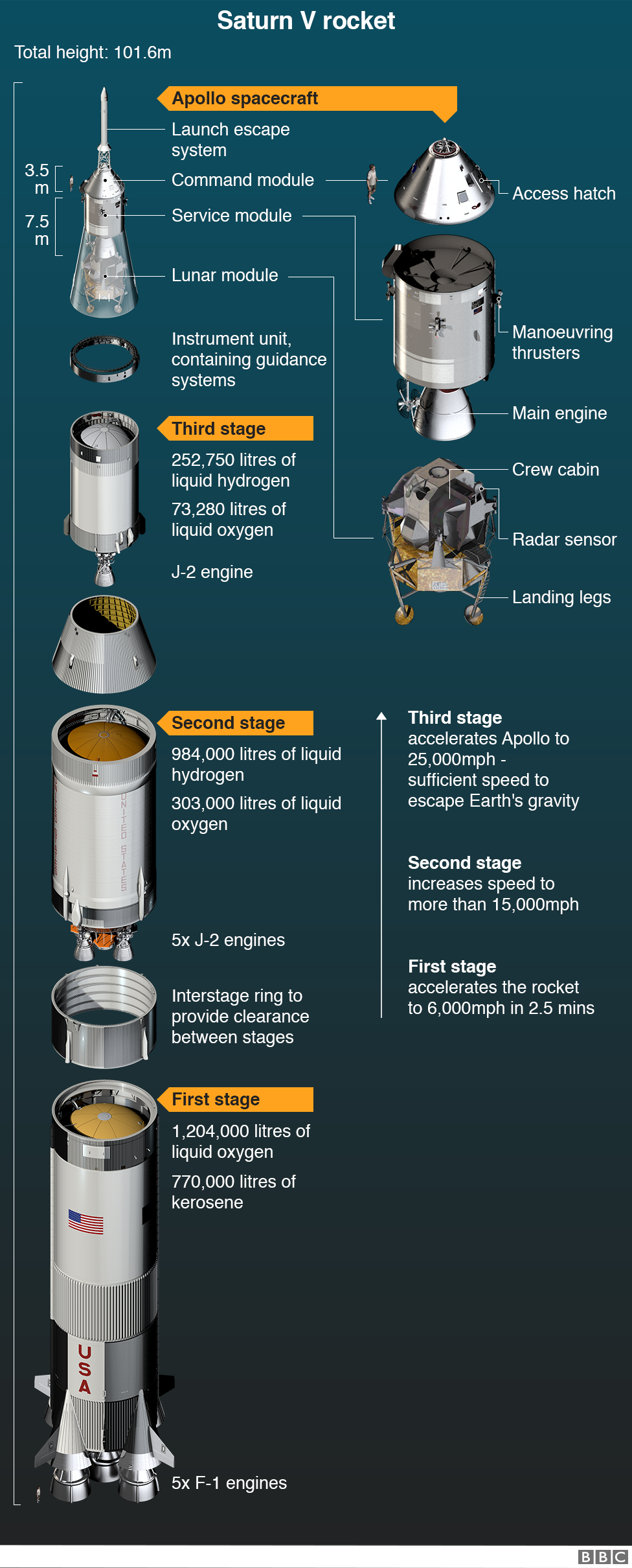

Having left Earth, Apollo performed a mid-flight turn to dock with the Lunar Module, which was carried into space behind the Command Module, before turning again and heading for the Moon.

3. African-American women skilled in maths helped to work out the route to the Moon

In the pre-digital age, Nasa employed a large number of female mathematicians as “human computers”. Many were African-Americans.

Their work processing data and performing complicated calculations was critical to the success of the space programme.

Image copyright

NASA

Katherine Johnson, pictured here in 1962, spent 33 years working for Nasa

When the first computers appeared, many of Nasa’s early programmers and coders were these women.

The film Hidden Figures, released in 2016, told the story of these maths wizards, bringing their stories to a mass audience for the first time.

One woman in particular, Katherine Johnson, became known for her work calculating trajectories for the first Americans in space, Alan Shepard and John Glenn, and later for the Apollo Lunar Module and Command Module on flights to the Moon.

Apollo 11’s flight path took the spacecraft into Earth orbit 11 minutes after launch.

Just over two hours later, during its second orbit, the rocket’s third stage fired again to boost Apollo towards the moon – the so-called Trans Lunar Insertion or TLI.

The TLI placed Apollo on a “free-return trajectory” – often illustrated as a figure of eight shape.

This course would have harnessed the power of the Moon’s gravity to propel the spacecraft back to Earth without the need for more rocket fuel.

However, when Apollo 11 neared its destination, astronauts performed a braking manoeuvre known as “lunar orbit insertion” to slow the spacecraft and cause it to go into orbit around the Moon.

From there, Armstrong and Aldrin descended to the surface.

4. No-one knows where the Apollo 11 module is now

A total of 10 lunar modules were sent into space and six landed humans on the moon.

Image copyright

NASA

Apollo 11’s Lunar Module ‘Eagle’ begins its descent to the lunar surface

Once used, the ascent stages of the capsules were jettisoned and either crash-landed on the moon, burned up in Earth’s atmosphere, or – in one instance – went into orbit around the Sun.

But where exactly they ended up is not known in every case.

What happened to the Lunar Modules?

The first two Lunar Modules were used in test flights and burned up in Earth’s atmosphere.

Apollo 10’s Lunar Module, which went to the Moon but didn’t land, was jettisoned into space and went into orbit around the Sun.

Astronomers recently disclosed they were “98% sure” they had located the drifting capsule – named Snoopy – some 50 years after its last sighting.

Image copyright

NASA

Apollo 13’s Lunar Module performed a vital “lifeboat” role when that mission had to be aborted following an explosion.

Most of the other modules – once they had safely returned astronauts back to the Command Module in lunar orbit – were dispatched to crash-land back on the surface.

The crash sites of most are known – but no-one is quite sure where the ascent stages of Apollo 11’s module Eagle or Apollo 16’s module Orion ended up.

By Tom Housden, Paul Sargeant and Lilly Huynh