If you ever want to stump a baseball fan, ask her to pick just one favorite line from Ball Four, Jim Bouton’s incredible diary of the 1969 MLB season.

For me, it’s actually a line of his about the book’s reception that perfectly encapsulates Bouton’s approach to writing, to many of the sport’s sacred cows, and to his own foibles:

“I can still remember Pete Rose, on the top step of the dugout screaming, ‘Fuck you, Shakespeare.’”

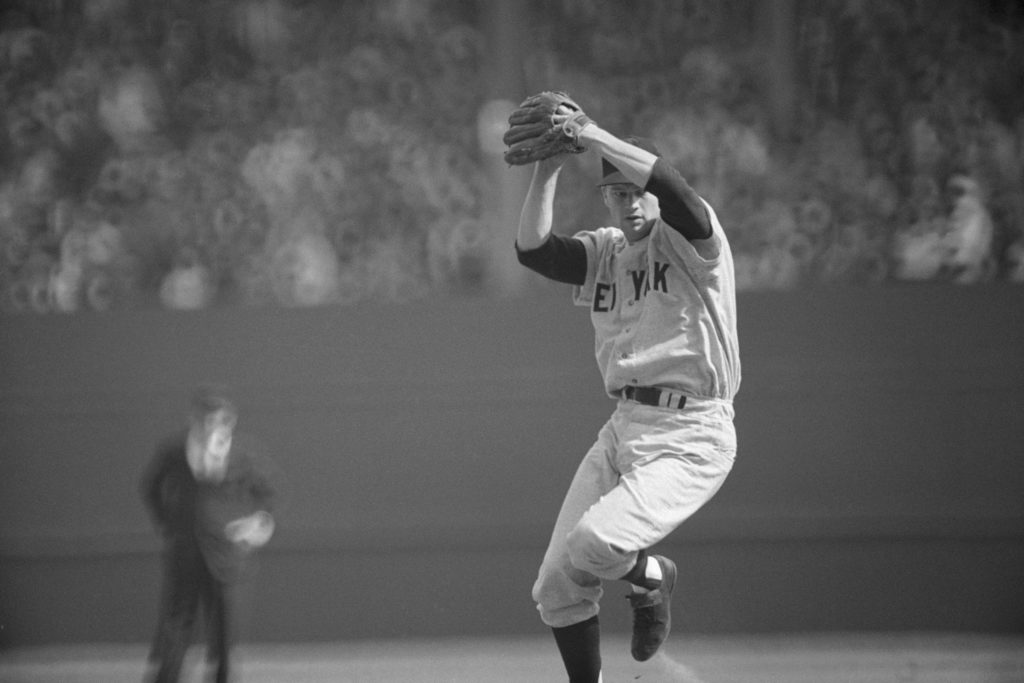

Bouton died on Wednesday at the age of 80, after a long and painful battle with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. The legacy he left behind is unlike any other forged by a professional athlete.

Before Ball Four, the accounts we got of professional athletes tended to be laced with reverence, their accomplishments placed on pedestals. Their home runs were majestic, their strikeouts heroic. Hagiographies were the norm.

Ball Four turned all of that on its head. Throughout baseball history, ballplayers practiced certain behaviors and traditions that never got reported by the press or repeated in polite company. Bouton, a very good pitcher for three seasons and a very ordinary one for a bunch more, was shackled with no such restrictions when he detailed his exploits for the ‘69 Seattle Pilots and Houston Astros, as well as previous seasons pitching for the Yankees.

One of the book’s most famous stories chronicles Mickey Mantle striding to the plate one day while fighting a hellacious hangover. His manager Ralph Houk gave him the day off, letting his star center fielder sleep off the aftereffects in the trainer’s room … until a 10th-inning spot required a pinch-hitter. Mantle shuffled to the plate, took a practice swing, and hammered a ball into the bleachers, winning the game for the Yankees.

A writer who knew Mantle’s condition when he came up to bat (but wouldn’t dare spill the beans to his readers) asked after the game: “‘Mick, how did you do that?’ …And he said, ‘Well, it was very simple. I hit the middle ball.’”

Whatever happened in the clubhouse was supposed to stay in the clubhouse, but it seemed no one had bothered to tell the sharp-witted, lanky right-hander that. Bouton matter-of-factly tore down the clubhouse’s fourth wall, doing so in a way that knocked readers for a loop when Ball Four came out in 1970, and still resonated with readers two and three generations later.

The backlash that engulfed alleged PED use by modern-day sluggers like Barry Bonds, Mark McGwire, and Sammy Sosa could look downright comical when viewed through the lens of Bouton’s writing decades earlier.

“At dinner Don Mincher, Marty Pattin and I discussed greenies,” Bouton wrote in reference to the performance-enhancing amphetamines that appeared in countless pre-game clubhouse spreads during the 60s. “They came up because O’Donoghue had just received a season supply of 500. ‘That ought to last about a month,’ I said.”

That same diary entry went on to assert that well over half the league popped amphetamines regularly, naming a couple of specific teams with a particularly high percentage of users.

What you believe Bouton’s intent was when telling these stories depends on how you want to interpret the book. Years after writing it, Bouton said he told the Mantle story with much of that same reverence shown by sportswriters of his time: It was an amazing coup to hit a tape-measure homer with the game on the line when the Mick couldn’t see straight, not anything to be ashamed of.

Reactions to the book within the game weren’t nearly as charitable. Fellow players ostracized him for daring to write so honestly about them. The ripple effect of the tell-all book would even extend to Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who tried hard to bury it, then discredit it.

One of the criticisms of Ball Four was the implication that Bouton was a grudge holder who didn’t appreciate what he had. This wasn’t anywhere near the truth.

As cynical (and funny, and irreverent, and delightful) as the book was, its author always loved baseball. Read the memories shared by those who knew him, such as New York Times writer Tyler Kepner detailing a 2017 visit with an infirm Bouton, the wobbly ex-pitcher still insisting on having a catch. Or consider the most frequently quoted passage from the book.

“A ballplayer spends a good piece of his life gripping a baseball,” Bouton wrote, “and in the end it turns out that it was the other way around all the time.”

As a young baseball fanatic, I first read Ball Four around age 12. It had become an institution long, long before I discovered it. But no matter when you found it, it allowed you to feel like you were in on all the best jokes, all the juiciest stories.

Ball Four made you feel like you were hiding in a corner of the clubhouse, eavesdropping on Mantle and Maris and that ragtag Pilots team, lapping up every secret you were never supposed to hear. When you finished reading that final word, you felt that much cooler as you placed the book gently back on your nightstand. And that much more excited to crack it open again the next day.

(Top photo of Bouton: Bettmann / Getty Images)