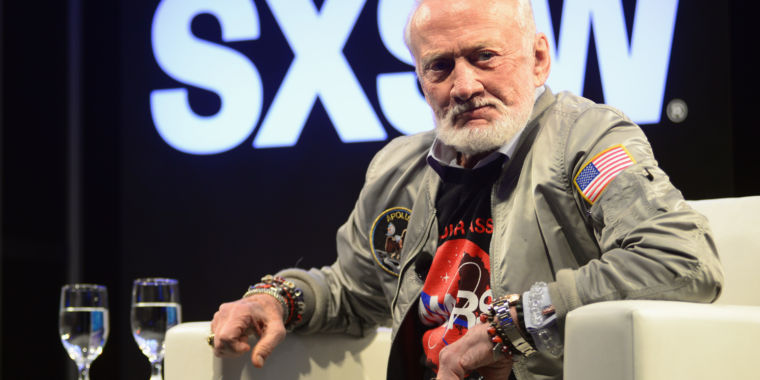

Hubert Vestil/Getty Images

Just after Memorial Day this year, I began talking regularly with the pilot of the first spacecraft to land on the Moon. We had spoken before, but this was different—it seemed urgent. Every week or two, Buzz Aldrin would call to discuss his frustration with the state of NASA and his concerns about the looming 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing without a lack of discernible progress to get back.

Even at 89, Aldrin remains remarkably engaged in the aerospace community, often showing up to meetings and conferences unannounced. Aldrin asks questions. He talks to the principals. In the last two years, the aerospace legend has been to the White House for major space announcements by President Trump, served as an adviser to the National Space Council, and supported the White House goal of returning to the Moon by 2024.

But what NASA has been doing to get back there, for the better part of two decades, just hasn’t been working. President Bush directed NASA back to the Moon more than 15 years ago, and in one form or another, NASA has been spending billions of dollars each year to build a big, heavy spacecraft and a bigger, much heavier rocket as the foundation for such a return. Along the way, NASA has enriched a half-dozen large aerospace contractors and kept Congress happy. But the space agency still can’t even launch its own astronauts into low-Earth orbit, let alone deep space or the Moon.

“I’ve been going over this in my mind,” Aldrin told Ars “We’ve been fumbling around for a long, long time. There has to be a better way of doing things. And I think I’ve found it.”

He realizes that, with a big Apollo anniversary on July 20, this may be one of his last chances to change things. You only hit a Golden Anniversary once, and then it’s gone. And soon, pretty quickly, so are you. So Buzz Aldrin would like to grab the spotlight at this moment, and in the process he hopes to finally get NASA moving forward. He wants NASA to stop trying to repeat the Apollo program of yesteryear and embrace the future of spaceflight.

So as we talked in late May and June, I simply took notes. Aldrin was not speaking to me, after all, he was trying to speak to the world.

Only a few left

Only a dozen humans have ever stepped out of a spacecraft and onto the surface of another world, and two-thirds of them are gone now. Aldrin’s partner on Apollo 11, Neil Armstrong, died in 2012. Pete Conrad, Alan Bean, Alan Shepard, Edgar Mitchell, Jim Irwin, John Young, and Gene Cernan have all gone away, too. Most died incredulous—how, they wondered, had the powerful legacy they left behind dissipated like a rocket’s contrail, scattered in the wind?

Of those still left to us, Aldrin is the oldest. Dave Scott, Charlie Duke, and Harrison Schmitt are all in their mid-80s. There is no guarantee any of them will be alive for the 60th anniversary of Apollo 11.

-

This is the official NASA portrait of astronaut Edwin E. (Buzz) Aldrin, who joined NASA in 1963. Prior to this, Aldrin flew 66 combat missions in F-86s while on duty in Korea.

NASA -

On November 11, 1966, Aldrin launched into space aboard the Gemini 12 spacecraft on a four-day flight, which brought the Gemini program to a successful close. Command pilot James A. Lovell is followed by Aldrin. The signs on their backs note this mission is the final flight of the Gemini Program.

NASA -

Aldrin performing a spacewalk during the Gemini 12 mission.

NASA -

Aldrin arrives at the Flight Crew Training building at the NASA Kennedy Space Center a few days prior to launch of Apollo 11.

-

Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong, second from left, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin eat breakfast with Donald “Deke” Slayton, in red shirt, on Apollo 11 launch day, July 16, 1969.

NASA -

In an iconic photo, Buzz Aldrin salutes the US flag on the Moon in 1969.

NASA -

The iconic footprint on the Moon photo? That’s Buzz’s.

NASA -

President Richard Nixon visits the crew of Apollo 11, in quarantine, after their return from the Moon.

NASA -

On July 20, 1984, President Reagan marks Space Exploration Day with the crew of Apollo 11.

NASA -

Aldrin visits Space Camp in 1996. That year he co-authored the science fiction book Encounter with Tiber.

Maria Garcia -

At the opening of Kennedy Space Center’s Apollo/Saturn V Center in 1997. The astronauts are (from left): Apollo 14 Lunar Module Pilot Edgar D. Mitchell; Apollo 10 Command Module Pilot and Apollo 16 Commander John W. Young; Apollo 11 Lunar Module Pilot Edwin E. “Buzz” Aldrin, Jr.; Apollo 10 Commander Thomas P. Stafford; Apollo 10 Lunar Module Pilot and Apollo 17 Commander Eugene A. Cernan; and Apollo 9 Lunar Module Pilot Russell L. Schweikart.

NASA -

President Barack Obama poses with Apollo 11 astronauts, from left, Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins, and Neil Armstrong, Monday, July 20, 2009, in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, on the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing.

NASA -

In late 2009, at Walt Disney World’s Magic Kingdom in Orlando, Fla., Aldrin rides in a 1969 Camaro convertible to participate in a ticker-tape parade to welcome his namesake, toy space ranger Buzz Lightyear, home from space.

-

Aldrin and George Clooney on stage at the OMEGA ‘Lost In Space’ dinner to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the OMEGA Speedmaster, which has been worn by every piloted NASA mission since 1965, at Tate Modern on April 26, 2017 in London, England.

Mike Marsland/Getty Images for OMEGA -

US President Donald Trump gives the pen to Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin after signing an Executive Order to reestablish the National Space Council in the Roosevelt Room of the White House on June 30, 2017 in Washington, DC.

Olivier Douliery-Pool/Getty Images

To its credit, the Trump administration has injected NASA with a sense of urgency by setting the 2024 landing goal. In response to this, NASA has proposed the Artemis program, a campaign of 37 launches that culminates with the beginnings of a lunar base in a decade. While there are serious questions about the political saliency of this plan, Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin is more concerned about the technical problems.

NASA has spent $50 billion building the Orion spacecraft, Space Launch System rocket, and related exploration vehicles over the past 15 years. Orion is a capable deep space capsule, but it is also massive, weighing 26 tons along with its service module and large heat shield. For every Artemis mission, NASA proposes to launch this mass all the way to the Moon and back. At least Orion is reusable; by contrast the large, expendable SLS rocket will cost more than $1.5 billion per flight and require a standing army of contractors just to keep supply lines open for, at most, a single mission per year.

For all of the time and money invested in SLS and Orion, these vehicles lack the energy to fly a mission into low lunar orbit and back. Indeed, the engine powering Orion’s service module has less than one-third of the thrust of the Apollo propulsion system that flew Aldrin to the Moon in 1969. This is a major reason NASA intends to build a Lunar Gateway—a small space station—in a distant orbit around the Moon. From there, the Gateway will come no closer than 1,000km to the lunar surface and spend most of its seven-day orbit much farther away.

“One thing that surprises me is the lack of performance,” Aldrin said, discussing these vehicles NASA has spent so long developing. “It forces NASA into this weird orbit. And how long is SLS going to last until Blue Origin or SpaceX replaces it? Not long. How long is that heavy Orion spacecraft, with an under-powered European service module, going to hang around in the inventory? Not long.”

Bullish momentum persists, S&P 500 sustains break to uncharted territory