Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Getty Images Plus.

Is Twitter “making” us stupid? Are phones “making” us lonely? Do today’s kids have a lower tolerance for boredom, because screens? These kinds of freshman-essay, conventional-wisdom hypotheses about tech’s effects on our collective mental state can sometimes feel impossible to discuss in a productive way. The conversation is too broad; there are too many variables; it’s too alarmist and turns me into a knee-jerk contrarian. (Come on! Surely kids have always been distractible.) Undaunted by the challenge of talking about these matters intelligently, historians Luke Fernandez and Susan Matt have a new book, Bored, Lonely, Angry, Stupid: Changing Feelings About Technology, From the Telegraph to Twitter, that walks through a lot of complicated history and leaves you more confused than ever. In a good way.

The book wrestles with two big questions: How have American emotions changed over time? And how has technology aided and abetted those changes? The study of the kinds of emotions an entire nation has experienced over time faces huge definitional challenges. Even looking at people who lived at roughly the same time, the feeling we now describe as “boredom” meant one thing to Thomas Jefferson, who counseled his daughter to avoid the “ennui” of her privileged life through mental activity; something else to James Williams, a 19th-century black American who described the “gloomy monotony” of slavery; and something else to the young female workers at the Lowell, Massachusetts, mills, who angled for seats near the windows so they could break up the repetition of their tasks with glances at the river.

And how do you even measure rates of something like boredom over time? Emotions are necessarily self-reported, and reporters are communicating not only their feelings but also the way they’ve been taught to feel about those feelings. The question of whether technology “causes” changes in the human heart is at least as knotty. “Technology alone does not determine feelings, but the larger culture, of which it is one part, undeniably shapes them,” is the best Matt and Fernandez can do. It’s a mess! But the mess is fascinating.

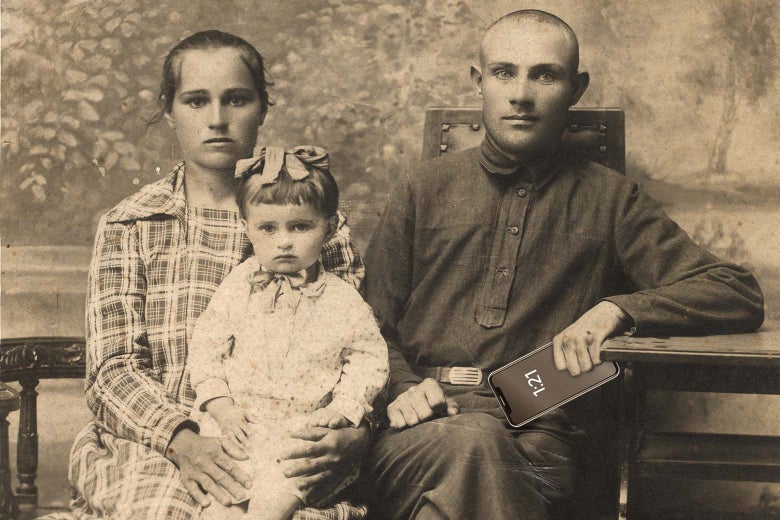

Example: The advent of accessible photography in the late 19th century did not “make” us more vain, or more interested in presenting our lives to others in a favorable light. But over time, the democratization of access to cameras seems to have combined with a million other big and small factors to have the same effect. Domestic photographs from the 19th century look weird to us because they’re so dark and sad, and the people are so unsmiling, Fernandez and Matt point out. In the 19th century, Fernandez and Matt write, grinning was seen as something for (they quote communications scholar Christina Kotchemidova) “peasants, drunkards, children, and halfwits.” This is why the portraits in the cult-classic book Wisconsin Death Trip look so creepy to contemporary audiences. Historian Nancy West has made the argument that, in the course of its early advertising campaigns, Kodak taught Americans how to present themselves as happy. It wasn’t until the 20th century that Americans learned to don that cheerful, “we’re doing great” look when cameras were around.

Cameras also “helped” 19th-century Americans accept more vanity in their personal presentation. A few photographers provided their clients with props and filters and modifications to help them “falsify” unattractive traits. Fernandez and Matt cite an 1892 source describing a Chicago photographer who profited from women’s desires to have shapely ankles and small feet by providing them with prosthetic substitutes—“shapely false limbs that could hang from the inner seams of the sitter’s dress.” While contemporary moralists challenged this new emphasis on worldly self-presentation, in the end, the camera’s proliferation carried the day.

As with Kodak’s advertising campaigns, technology companies’ efforts to sell the telephone and phonograph to late-19th-century consumers seem to have some relationship (causal? Correlational? Who knows!) to another emotional shift that happened around the same time. In this case, Americans seem to have gone from expecting to experience some degree of solitude in their lives to an active desire to avoid loneliness. Company advertisements hailed the telephone and the phonograph as antidotes for the feeling. Bell suggested putting in a phone for children who felt isolated at home: “A little girl can always get somebody to play with by using the Bell telephone. … There is no need to be lonesome with a telephone in the house.”

It was around the turn of the 20th century that “awe fell out of fashion.”

So much of the pivot point of change in the emotions Fernandez and Matt describe seems to come around the turn of the 20th century—right when revolutions in transportation and communication were cresting, urbanization was proceeding at a rapid clip, and American consumerism was gearing up for its heyday. The authors cite historian Thomas Haskell’s idea of a “recession of causation” to explain the change in people’s worldviews around this time. Americans used to being able to understand their worlds mostly via talking to their neighbors found themselves in a world of much larger networks of material and knowledge, where things happening far away and out of their control had deep effects on their lives.

Because of their growing sense that circumstances were out of their control, Fernandez and Matt argue, Americans began to believe that they needed to focus ever-more intently in order to succeed in the world. Early psychologists were fascinated by questions of attention and distraction, and “success advisers” of the time advised concentration above all. One of those, T. Sharper Knowlson, wrote that the difference between “men who are leading in business, finance, and the profession” and “those fellows who lag behind” was “the intensity of their thought-forces.” (That’s a ready-made headline for a Medium life-hacking post, if you ask me.)

It was around the turn of the 20th century, too, that “awe fell out of fashion,” “for psychologists considered it a backward, premodern feeling.” Fernandez and Matt point to instances in which some people in the 19th century seem to have truly thought that the technologies of the telegram and telegraph would allow them to speak to dead people. As the telephone and telegram faded into the background of American life, these ideas, inspired by the awesome nature of these technologies, soon began to look antiquated and silly. As early as 1869 a poet declared that the telegraph had ruined wonder for Americans—in a good way: “No more the hours of awe and gloom, [w]hich filled our childish hearts with dread. … Now science grabs the lightning fire.”

It’s not that technologies of transportation and communication didn’t affect Americans’ emotional style before the late 19th century—Fernandez and Matt note that the partisan, inflammatory newspapers of the early republic seem to have reflected and amplified political dissension. On this matter they quote historian David Nord, who wrote: “When Americans in the early Republic saw treason, sedition, fragmentation, dissension, degeneration, disunion, anarchy, and chaos, they usually saw it first in the newspaper.” White men, who could afford to show fury publicly, also got together to get angry in person. American town folk held local “indignation meetings” throughout the 19th century, protesting causes as big as the continued institution of slavery, as local as the verdict in a murder trial, or as specific as the University of Michigan’s 1849 expulsion of students who belonged to secret societies.

In the case of anger, Fernandez and Matt argue, the turn of the 20th century actually brought a tamping down of the emotion in face-to-face, day-to-day public life. Numbers of people working for corporations in offices rose, and the ability to control one’s temper around co-workers and subordinates became paramount for those who aspired to management status. But at the same time, the advent of the radio seems to have given some of that submerged rage an ethereal outlet. As early as 1935, scholars believed that the radio would create a “crowd mentality,” or a “mob spirit,” that could be dangerous.

Populist and fascist sympathizer Father Charles Coughlin’s radio broadcasts provoked letters to the Federal Communications Commission and to the president, from citizens who feared that Coughlin provoked too much anger in their fellow citizens. The existence of Coughlin’s broadcasts made some of these people worry that the technology of radio itself was inherently dangerous. In 1939, a Jewish resident of Chicago, Dorothy Omens, wrote: “I’ve sat for three days now in my home listening to these broadcasts and staring into my radio. Can one hate a piece of wood? Yet my lovely modern radio looks despicable to me. My favorite programs have lost their significance and sound like mockery.”

Despite many instances in which more powerful technologies of communication seem to have coincided with an increase in negative emotions of anger, loneliness, and stress, the authors try to end the book on a positive note: “In some ways, the new American emotional style we have been experiencing and observing is a sign of emotional liberation and democracy. … Self-presentation, self-adoration, and aggrandizement are now rights we all share.” The communal anger people now show on social media is something of a throwback to the 19th century’s indignation meetings—with the important difference that now, women and minorities are much freer to participate. (They’re still not, I would argue, completely free to rage without blowback from the many white men who still see anger as their exclusive province, but there is much more room.) “Awe is a weaker emotion,” the authors write, “and when Americans express it, it is often in reaction to themselves and their own creations. Its former power, as a check on hubris and vanity, has largely disappeared.”

It feels impossible for historians to argue much of anything when it comes to a nation’s changing emotions, because the topic is too big, too nebulous, too out-of-control. That becomes clear in the sections of the book where the two historians interview present-day Americans about their feelings about social media—an attempt at bringing the story up to 2019, but the sample is quite small, and the observations feel both self-conscious and (for lack of a better word) basic. One person interviewed in their section on attention said: “You go on to CNN, you got things blinking at you. It’s trying to grab your attention, it’s competing for your attention.” On boredom, another contributed: “Every time I’m bored I pull up my phone and the first thing I do is Instagram and scroll through it until I catch up to where I was. Then I pull up Facebook. And it’s like a pattern, it’s like a habit. Yet I still feel bored.”

Despite being fairly flat, these sections are still instructive. They show how little we really know about how angry or awed or bored people truly were before and after the telegram or the radio. We have scattered evidence of people’s self-reported reactions, the funhouse mirror of consumer and popular culture, and the deeper work of contemporary intellectuals, academics, and scientists who perceived shifts as they were happening—but who had a professional stake in arguing their points of view. That’s the nature of the beast. Maybe by 2060, historians who are interested in finding out whether we really did get more short-tempered around 2006, when Twitter was invented, will have better tools to more precisely mine our tweets and posts for our sentiments. If, that is, our distracted rage doesn’t kill us first.

Harvard University Press

By Luke Fernandez and Susan Matt. Harvard University Press.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers.

If you buy something through our links,

Slate may earn an affiliate commission.

We update links when possible,

but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change.

All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Future Tense

is a partnership of

Slate,

New America, and

Arizona State University

that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.